Social Justice

Rethinking India’s Nutrition Strategy

- 17 Mar 2025

- 22 min read

This editorial is based on “Tackling the problem of nutrition” which was published in The Hindu on 17/03/2025. The article brings into focus India's nutrition challenge, which extends beyond food insecurity to cultural, gender, and health factors.

For Prelims: Public Distribution System, Saksham Anganwadi, Poshan 2, Integrated Child Development Services, Green Revolution, National Nutrition Policy, Mid-Day Meal Scheme, Universal Immunization Programme, National Food Security Act (NFSA) (2013), One Nation, One Ration Card, Global Hunger Index, NFHS-5 report, One Nation, One Ration Card, Farmer Producer Organizations .

For Mains: Evolution of Nutritional Security Programmes in India, Issues Leading to Nutritional Insecurity in India.

India's nutrition challenge extends beyond food insecurity, encompassing cultural habits, gender relations, and diet-induced diseases across all demographics. While Budget 2025 increases funding for Saksham Anganwadi and Poshan 2.0, these programs maintain a narrow focus on maternal and child malnutrition, overlooking other vulnerable groups. There is a need for a comprehensive nutrition agenda that recognizes diverse nutritional needs, leverages local food systems, and utilizes health and wellness centers as delivery mechanisms.

How Nutritional Security Programmes Evolved in India?

- Post-Independence Era (1950s-1970s): Food Sufficiency & Basic Nutrition Support

- In the early years, India faced severe food shortages, famine risks, and widespread malnutrition, prompting a food security-first approach.

- The government’s priority was to increase agricultural production and ensure minimum food availability for the masses.

- Nutrition-specific policies were limited, primarily focusing on targeted feeding programs for children and mothers.

- Key Initiatives:

- Public Distribution System (PDS) (introduced around World War II, expanded post-1947): Provided subsidized staple grains to address food insecurity.

- ICDS (1975): Integrated Child Development Services launched to provide supplementary nutrition, immunization, and preschool education to children under 6 and pregnant/lactating mothers.

- Balwadi Nutrition Programme (1970s): Provided nutritional supplements to preschool children in rural areas.

- In the early years, India faced severe food shortages, famine risks, and widespread malnutrition, prompting a food security-first approach.

- Green Revolution & Expansion of Food-Based Schemes (1980s-1990s)

- With the Green Revolution (1960s-70s) ensuring food self-sufficiency, attention shifted to expanding social welfare programs for nutrition.

- The government institutionalized nutrition programs within healthcare and education systems, recognizing that malnutrition persisted despite food availability.

- Key Initiatives:

- Mid-Day Meal Scheme (MDMS) (1995, formalized under Supreme Court directive in 2001): Provided cooked meals to schoolchildren, improving nutrition and school enrollment.

- National Nutrition Policy (1993): Introduced a multi-sectoral approach, integrating agriculture, health, and food distribution for better nutritional outcomes.

- Universal Immunization Programme (1985): Helped combat nutrient deficiencies linked to infections.

- With the Green Revolution (1960s-70s) ensuring food self-sufficiency, attention shifted to expanding social welfare programs for nutrition.

- Rights-Based Approach & Micronutrient Interventions (2000s-2010s)

- The 2000s saw a paradigm shift from welfare-based nutrition support to rights-based food security and micronutrient interventions.

- The government recognized hidden hunger (micronutrient deficiencies) and the need for a legal framework to ensure universal food access.

- Key Initiatives:

- National Food Security Act (NFSA) (2013): Made PDS as legal entitlements, ensuring food for upto 75% of the rural population and 50% of the urban population

- Iron & Folic Acid Supplementation (2013): Addressed widespread anaemia among women and children.

- Fortification Programs: Launched fortified rice, wheat, and milk distribution to tackle hidden hunger.

- POSHAN Abhiyaan (erstwhile National Nutrition Mission): It was launched in March 2018 to achieve improvement in nutritional status of Children from 0-6 years.

- The 2000s saw a paradigm shift from welfare-based nutrition support to rights-based food security and micronutrient interventions.

- Comprehensive Nutrition & Health Integration (2020s - Present)

- India’s latest approach combines nutrition, healthcare, agriculture, and behavioral change, recognizing that malnutrition is not just about food availability but also quality, affordability, and awareness.

- The government is now leveraging digital technology, local food systems, and climate-resilient agriculture for better nutritional outcomes.

- Key Initiatives:

- Poshan 2.0 (2022): Merged ICDS, Mid-Day Meal, and Poshan Abhiyaan for a life-cycle approach to nutrition.

- Millets Promotion under International Year of Millets (2023) – Encouraged nutrient-rich, climate-resilient crops in PDS, Mid-Day Meals, and ICDS.

- One Nation, One Ration Card (ONORC): Ensured migrant workers could access subsidized food anywhere in India.

- Health & Wellness Centres (Ayushman Bharat): Integrated nutrition counseling, non-communicable disease prevention, and lifestyle interventions into primary healthcare.

- India’s latest approach combines nutrition, healthcare, agriculture, and behavioral change, recognizing that malnutrition is not just about food availability but also quality, affordability, and awareness.

Why does India Continue to Grapple with Nutritional Insecurity?

- Persistent Child Malnutrition and Anaemia: India's excessive focus on food security has not translated outcomes away from nutritional security, leading to high child malnutrition and anemia.

- Poverty, lack of dietary diversity, and poor maternal health continue to affect early childhood nutrition.

- NFHS-5 (2019-21), 36% of children under five are stunted and 57% of women (15-49) are anaemic.

- Even in key hunger indicators like Global Hunger Index (GHI) 2023, India ranks 111 out of a total of 125 countries.

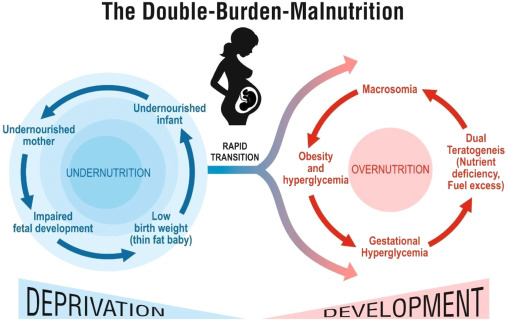

- Double Burden of Malnutrition- Obesity & NCDs: While undernutrition persists, urbanization and changing food habits have led to rising obesity and diet-induced non-communicable diseases (NCDs) like diabetes and hypertension.

- High consumption of processed, sugar-laden foods and a sedentary lifestyle have worsened the health crisis (Economic Survey 2023-24).

- Despite this, nutrition policies remain focused on calorie intake rather than dietary quality.

- Affordable, healthy food remains out of reach for many, while junk food is cheap and accessible.

- Almost one-fourth of our population (both men and women) are currently either overweight or obese in India

- In India, there are estimated 77 million people above the age of 18 years are suffering from diabetes (type 2) and nearly 25 million are prediabetics.

- Gender and Social Disparities in Nutrition Access: Nutrition security in India is deeply affected by gender discrimination, caste hierarchies, and social inequalities.

- Women, especially in rural areas, eat last and least in households, leading to widespread micronutrient deficiencies.

- Government programs primarily target pregnant women but ignore adolescent girls and elderly women.

- According to the NFHS-5 report, there was no significant improvement in health and nutritional status among women in India

- Climate Change and Agricultural Distress: Extreme weather events like heat waves, erratic monsoons, and droughts have impacted crop yields, food prices, and dietary diversity.

- Climate-induced food insecurity is worsening in vulnerable regions like Bihar, Odisha, and Madhya Pradesh, exacerbating hunger and undernutrition.

- India recorded its warmest February in 124 years this year, affecting rabi wheat yields.

- Also, recent government data highlight that India's rice and wheat production is expected to decline by 6-10% due to climate change.

- Climate-induced food insecurity is worsening in vulnerable regions like Bihar, Odisha, and Madhya Pradesh, exacerbating hunger and undernutrition.

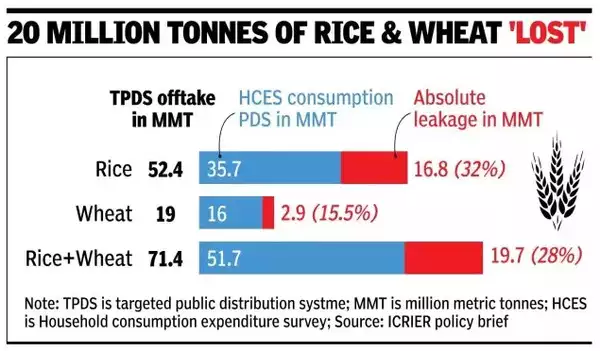

- Weak Implementation of Nutrition Programs: Despite schemes like Mid-Day Meal (PM POSHAN), Saksham Anganwadi, and Food Fortification, leakages, poor implementation, and exclusion errors weaken their impact.

- Many Anganwadi Centres lack trained staff, and take-home rations are often substandard.

- The urban poor and migrant workers remain outside formal nutrition safety nets, leaving them vulnerable to hidden hunger and food insecurity.

- A new study reveals that nearly 28% of India's subsidized grains, intended for the poor, are lost to leakage, costing the government an

- A recent CAG report highlights the absence of basic amenities such as toilets and drinking water at many Anganwadi Centres (AWCs) that put the young children in unhygienic conditions.

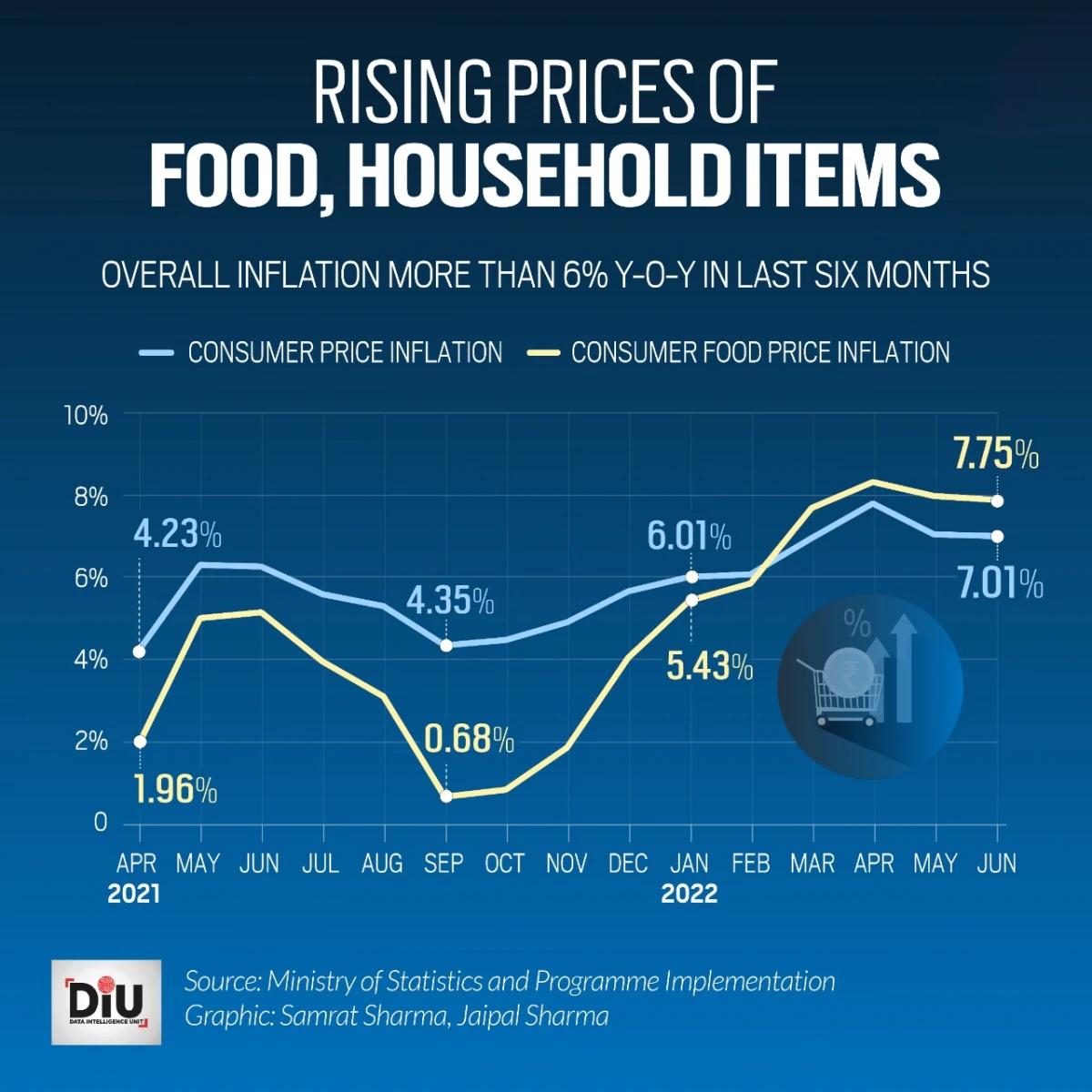

- Economic Inequality and Rising Food Prices: The economic slowdown, post-pandemic inflation, and global supply chain disruptions have made nutritious food expensive, disproportionately impacting low-income households.

- While free grain distribution under PM Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana ensures caloric sufficiency, it does not address protein, vitamin, and mineral deficiencies.

- Many Indians are full but malnourished due to poor dietary choices and limited affordability of healthy foods.

- Retail food inflation ruled above 8% from November 2023 to June 2024, with pulses and vegetables great spikes.

- Urban Food Deserts and Poor Dietary Diversity: Rapid urbanization has created "food deserts"—areas where affordable, nutritious food is scarce, but fast food is abundant.

- Low-income urban families, especially migrant workers and daily wage laborers, struggle to access fresh fruits, vegetables, and proteins, relying on cheap, processed, and calorie-dense foods.

- This worsens both micronutrient deficiencies and obesity, increasing the burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs).

- As much as 68% of food and beverage products currently available in the Indian food market have excess amounts of at least one ingredient of concern like high sugar, high salt and trans fat.

- Low-income urban families, especially migrant workers and daily wage laborers, struggle to access fresh fruits, vegetables, and proteins, relying on cheap, processed, and calorie-dense foods.

- Weak Public Awareness and Behavioral Challenges: Despite government efforts, nutritional awareness remains low, and food choices are often dictated by cultural preferences, misinformation, and marketing.

- Many households prioritize taste, tradition, and affordability over nutritional value.

- School curriculums and public campaigns lack a strong focus on everyday nutrition education.

- For instance, 85% of Indians are unaware of vegetarian sources of protein, while more than 50% are unaware of healthy fats.

- Many households prioritize taste, tradition, and affordability over nutritional value.

What Measures India Can Adopt to Enhance Nutritional Security?

- Strengthening HWCs for Community-Led Nutrition: Health & Wellness Centres should be upgraded into Nutrition Resource Centres, providing personalized diet counseling, regular screenings for malnutrition and NCDs, and locally tailored meal plans.

- By integrating Poshan 2.0 with Ayushman Bharat HWCs, nutrition services can be expanded beyond maternal health to include adolescents, the elderly, and NCD patients.

- Dedicated community nutrition officers can bridge the gap between healthcare and dietary interventions, ensuring nutrition becomes a core part of public health services.

- Revamping Mid-Day Meals with Local Food Systems: The Mid-Day Meal Scheme should emphasize regionally available, nutrient-rich foods like millets, pulses, and leafy greens, reducing dependence on staple grains like rice and wheat.

- A decentralized approach, involving local SHGs (Self-Help Groups) and Farmer Producer Organizations (FPOs), can ensure fresh, diverse, and culturally relevant meals for children.

- Integrating PM-POSHAN with the Millets Mission will help promote nutritionally superior grains while boosting rural livelihoods.

- Mandatory Fortification with a Focus on Micronutrient Deficiency: Scaling up fortification of staple foods like rice, wheat, milk, and edible oils can combat hidden hunger without altering eating habits.

- Linking the Public Distribution System (PDS) with fortified food distribution will ensure even low-income groups receive essential vitamins and minerals.

- However, fortification should be complemented with dietary diversification, ensuring that natural sources of nutrients are not neglected.

- Making Urban Food Environments Healthier: A graded taxation system on ultra-processed, high-sugar, and trans-fat-laden foods can curb unhealthy eating habits while promoting affordable healthy alternatives.

- Zoning laws can be introduced to restrict fast-food outlets near schools and healthcare facilities, nudging people toward healthier choices.

- Linking the Eat Right India movement with the FSSAI Front-of-Pack Labeling (FOPL) initiative will ensure consumers are well-informed about the nutritional quality of their food choices.

- Climate-Smart Agriculture for Nutritionally Resilient Food Production: India must shift from calorie-heavy monoculture farming (rice & wheat) toward nutrient-dense, climate-resilient crops like millets, pulses, and biofortified varieties.

- Policies like the National Food Security Act (NFSA) should be amended to include millets in the PDS, incentivizing farmers to diversify crops.

- Watershed management, agroforestry, and regenerative farming should be scaled up to enhance soil health and ensure nutrient-rich food production despite climate challenges.

- Expanding Social Protection Schemes: PDS should move beyond just providing caloric sufficiency and focus on nutritional adequacy by including pulses, millets, and fortified dairy products.

- Expanding Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) to include adolescent girls and elderly women will address lifelong nutritional vulnerabilities.

- Linking DBT (Direct Benefit Transfer) with nutrition support for vulnerable populations, such as migrant workers and urban poor, will ensure flexibility in dietary choices while maintaining food security.

- Mass Nutrition Literacy Campaigns: A nationwide "Right to Nutrition" campaign, integrated into school curriculums, workplaces, and social media, can build awareness about balanced diets, food labeling, and unhealthy food risks.

- Engaging influencers, faith-based organizations, and community leaders will help counter myths about food choices, especially among marginalized groups.

- Expanding Eat Right India into a year-round grassroots movement will reinforce healthy dietary habits from childhood.

What are the Key Best Practices of Indian States Related to Nutrition?

- Chhattisgarh: Multi-Sectoral Approach for Stunting Reduction

- Stunting declined from 52.9% to 37.6% (2006-2016) due to improvements in health services, sanitation, and household assets.

- Strong political stability, bureaucratic efficiency, and community mobilization helped scale up interventions.

- Gujarat: Strengthening Policy for Nutrition Outcomes

- Stunting dropped from 51.7% to 38.5% (2006-2016), driven by an enabling policy environment and improved maternal and child health interventions.

- Expanding women’s education, WASH (Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene), and rural development played a crucial role.

- Odisha: Steady Progress Through Policy & Partnerships

- Stunting fell from 45% to 34.1%, with strong political commitment and policy support driving change.

- Convergence of state, development partners, and financial resources helped scale up nutrition programs.

- Challenges like poor sanitation, early marriage, and education gaps still need urgent attention.

- Tamil Nadu: A Long-Term Vision for Nutrition

- Tamil Nadu achieved historic success in reducing undernutrition between 1992-2016 through investments in social welfare, health, and gender equality.

- The state's focus on women's welfare and child development remains a key success factor.

Conclusion:

India must move beyond food security to holistic nutritional well-being, aligning with SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) and SDG 3 (Good Health & Well-being). Strengthening Health & Wellness Centres, promoting local food systems, and addressing malnutrition across all demographics can bridge policy gaps. A community-driven, climate-smart, and inclusive approach is key to achieving sustainable nutrition security for all.

|

Drishti Mains Question: Despite various government initiatives, India's nutritional security remains a challenge due to systemic gaps beyond food availability. Analyze the key issues and suggest a multi-pronged strategy to ensure holistic nutritional well-being? |

UPSC Civil Services Examination Previous Year’s Question (PYQs)

Prelims:

Q. Which of the following is/are the indicator/indicators used by IFPRI to compute the Global Hunger Index Report? (2016)

- Undernourishment

- Child stunting

- Child mortality

Select the correct answer using the code given below:

(a) 1 only

(b) 2 and 3 only

(c) 1, 2 and 3

(d) 1 and 3 only

Ans: (c)

Q. In the context of India’s preparation for Climate-Smart Agriculture, consider the following statements: (2021)

- The ‘Climate-Smart Village’ approach in India is a part of a project led by the Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), an international research programme.

- The project of CCAFS is carried out under Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) headquartered in France.

- The International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) in India is one of the CGIAR’s research centres.

Which of the statements given above are correct?

(a) 1 and 2 only

(b) 2 and 3 only

(c) 1 and 3 only

(d) 1, 2 and 3

Ans: (d)

Q. With reference to the provisions made under the National Food Security Act, 2013, consider the following statements: (2018)

- The families coming under the category of ‘below poverty line (BPL)’ only are eligible to receive subsidised food grains.

- The eldest woman in a household, of age 18 years or above, shall be the head of the household for the purpose of issuance of a ration card.

- Pregnant women and lactating mothers are entitled to a ‘take-home ration’ of 1600 calories per day during pregnancy and for six months thereafter.

Which of the statements given above is/are correct?

(a) 1 and 2 only

(b) 2 only

(c) 1 and 3 only

(d) 3 only

Ans: (b)

Mains

Q: Food Security Bill is expected to eliminate hunger and malnutrition in India. Critically discuss various apprehensions in its effective implementation along with the concerns it has generated in WTO. (2013)