Land Reforms in India

Pre Independence

- Under the British Raj, the farmers did not have the ownership of the lands they cultivated, the landlordship of the land lied with the Zamindars, Jagirdars etc.

- Several important issues confronted the government and stood as a challenge in front of independent India.

- Land was concentrated in the hands of a few and there was a proliferation of intermediaries who had no vested interest in self-cultivation.

- Leasing out land was a common practice.

- The tenancy contracts were expropriative in nature and tenant exploitation was almost everywhere.

- Land records were in extremely bad shape giving rise to a mass of litigation.

- One problem of agriculture was that the land was fragmented into very small parts l for commercial farming.

- It resulted in inefficient use of soil, capital, and labour in the form of boundary lands and boundary disputes.

- Land was concentrated in the hands of a few and there was a proliferation of intermediaries who had no vested interest in self-cultivation.

Post Independence

- A committee, under the Chairmanship of J. C. Kumarappan was appointed to look into the problem of land. The Kumarappa Committee's report recommended comprehensive agrarian reform measures.

- The Land Reforms of the independent India had four components:

- The Abolition of the Intermediaries

- Tenancy Reforms

- Fixing Ceilings on Landholdings

- Consolidation of Landholdings.

- These were taken in phases because of the need to establish a political will for their wider acceptance of these reforms.

Abolition of the Intermediaries

- Abolition of the zamindari system: The first important legislation was the abolition of the zamindari system, which removed the layer of intermediaries who stood between the cultivators and the state.

- The reform was relatively the most effective than the other reforms, for in most areas it succeeded in taking away the superior rights of the zamindars over the land and weakening their economic and political power.

- The reform was made to strengthen the actual landholders, the cultivators.

- Advantages: The abolition of intermediaries made almost 2 crore tenants the owners of the land they cultivated.

- The abolition of intermediaries has led to the end of a parasite class. More lands have been brought to government possession for distribution to landless farmers.

- A considerable area of cultivable waste land and private forests belonging to the intermediaries has been vested in the State.

- The legal abolition brought the cultivators in direct contact with the government.

- Disadvantages: However, zamindari abolition did not wipe out landlordism or the tenancy or sharecropping systems, which continued in many areas. It only removed the top layer of landlords in the multi-layered agrarian structure.

- It has led to large-scale eviction. Large-scale eviction, in turn, has given rise to several problems – social, economic, administrative and legal.

- Issues: While the states of J&K and West Bengal legalised the abolition, in other states, intermediaries were allowed to retain possession of lands under their personal cultivation without limit being set.

- Besides, in some states, the law applied only to tenant interests like sairati mahals etc. and not to agricultural holdings.

- Therefore, many large intermediaries continued to exist even after the formal abolition of zamindari.

- It led to large-scale eviction which in turn gave rise to several socio-economic and administrative problems.

- Besides, in some states, the law applied only to tenant interests like sairati mahals etc. and not to agricultural holdings.

Tenancy Reforms

- After passing the Zamindari Abolition Acts, the next major problem was of tenancy regulation.

- The rent paid by the tenants during the pre-independence period was exorbitant; between 35% and 75% of gross produce throughout India.

- Tenancy reforms introduced to regulate rent, provide security of tenure and confer ownership to tenants.

- With the enactment of legislation (early 1950s) for regulating the rent payable by the cultivators, fair rent was fixed at 20% to 25% of the gross produce level in all the states except Punjab, Haryana, Jammu and Kashmir, Tamil Nadu, and some parts of Andhra Pradesh.

- The reform attempted either to outlaw tenancy altogether or to regulate rents to give some security to the tenants.

- In West Bengal and Kerala, there was a radical restructuring of the agrarian structure that gave land rights to the tenants.

- Issues: In most of the states, these laws were never implemented very effectively. Despite repeated emphasis in the plan documents, some states could not pass legislation to confer rights of ownership to tenants.

- Few states in India have completely abolished tenancy while others states have given clearly spelt out rights to recognized tenants and sharecroppers.

- Although the reforms reduced the areas under tenancy, they led to only a small percentage of tenants acquiring ownership rights.

Ceilings on Landholdings

- The third major category of land reform laws were the Land Ceiling Acts. In simpler terms, the ceilings on landholdings referred to legally stipulating the maximum size beyond which no individual farmer or farm household could hold any land. The imposition of such a ceiling was to deter the concentration of land in the hands of a few.

- In 1942 the Kumarappan Committee recommended the maximum size of lands a landlord can retain. It was three times the economic holding i.e. sufficient livelihood for a family.

- By 1961-62, all the state governments had passed the land ceiling acts. But the ceiling limits varied from state to state. To bring uniformity across states, a new land ceiling policy was evolved in 1971.

- In 1972, national guidelines were issued with ceiling limits varying from region to region, depending on the kind of land, its productivity, and other such factors.

- It was 10-18 acres for best land, 18-27 acres for second class land and for the rest with 27-54 acres of land with a slightly higher limit in the hill and desert areas.

- With the help of these reforms, the state was supposed to identify and take possession of surplus land (above the ceiling limit) held by each household, and redistribute it to landless families and households in other specified categories, such as SCs and STs.

- Issues: In most of the states these acts proved to be toothless. There were many loopholes and other strategies through which most landowners were able to escape from having their surplus land taken over by the state.

- While some very large estates were broken up, in most cases landowners managed to divide the land among relatives and others, including servants, in so-called ‘benami transfers’ – which allowed them to keep control over the land.

- In some places, some rich farmers actually divorced their wives (but continued to live with them) in order to avoid the provisions of the Land Ceiling Act, which allowed a separate share for unmarried women but not for wives.

Consolidation of Landholdings

- Consolidation referred to reorganization/redistribution of fragmented lands into one plot.

- The growing population and less work opportunities in non- agricultural sectors, increased pressure on the land, leading to an increasing trend of fragmentation of the landholdings.

- This fragmentation of land made the irrigation management tasks and personal supervision of the land plots very difficult.

- This led to the introduction of landholdings consolidation.

- Under this act, If a farmer had a few plots of land in the village, those lands were consolidated into one bigger piece of land which was done by either purchasing or exchanging the land.

- Almost all states except Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Manipur, Nagaland, Tripura and parts of Andhra Pradesh enacted laws for consolidation of Holdings.

- In Punjab and Haryana, there was compulsory consolidation of the lands, whereas in other states law provided for consolidation on voluntary basis; if the majority of the landowners agreed.

- Advantages: It prevented the endless subdivision and fragmentation of land Holdings.

- It saved the time and labour of the farmers spent in irrigating and cultivating lands at different places.

- The reform also brought down the cost of cultivation and reduced litigation among farmers as well.

- Result: Due to lack of adequate political and administrative support the progress made in terms of consolidation of holding was not very satisfactory except in Punjab, Haryana and western Uttar Pradesh where the task of consolidation was accomplished.

- However, in these states there was a need for re-consolidation due to subsequent fragmentation of land under the population pressure.

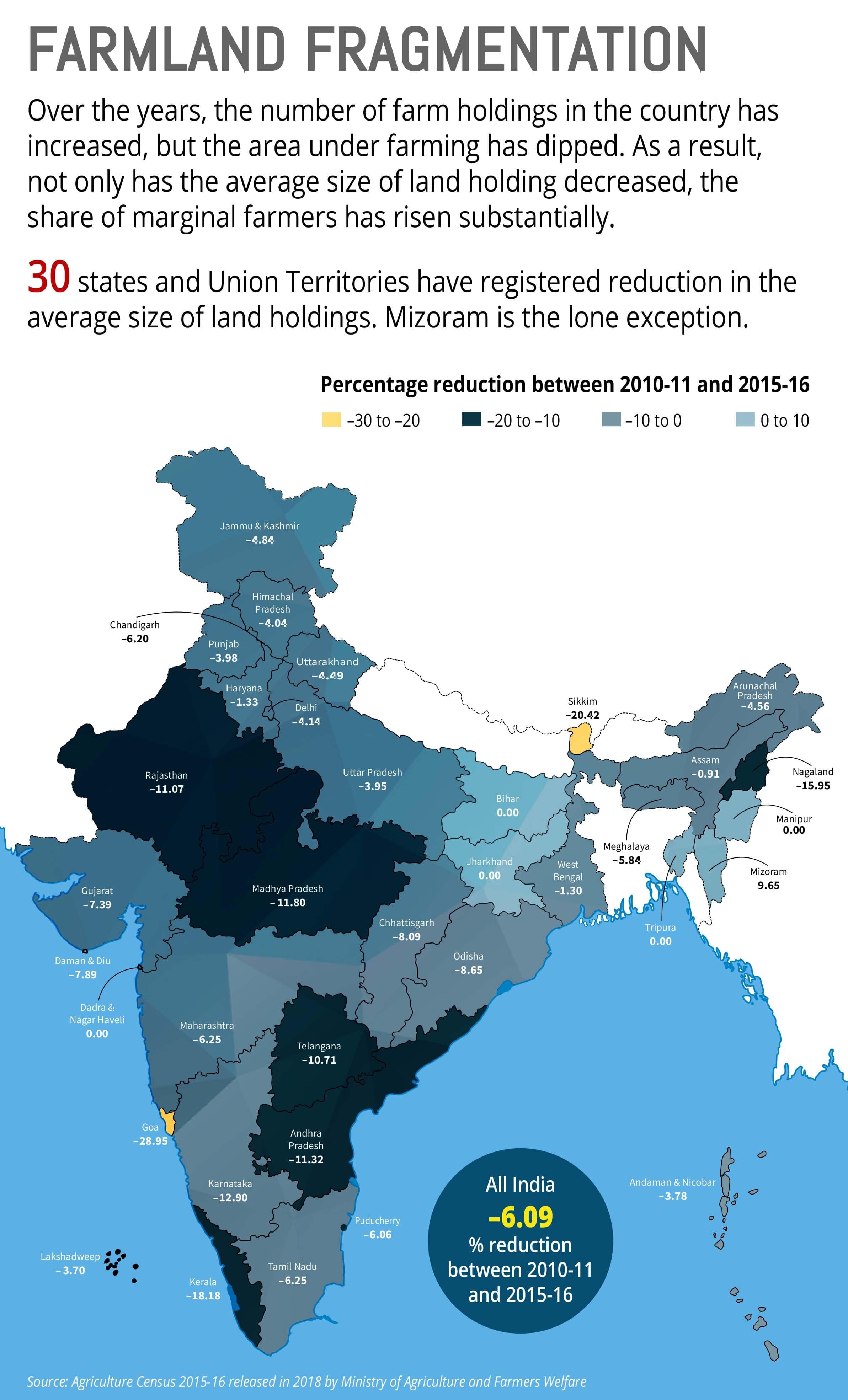

- Need of re-consolidation: The average holding size in 1970-71 was 2.28 hectares (Ha), which has come down to 1.08 Ha in 2015-16.

- While Nagaland has the largest average farm size, Punjab and Haryana rank second and third in the list respectively.

- The holdings are much smaller in densely populated states like Bihar, West Bengal and Kerala.

- The multiple subdivisions across generations have reduced even the sub divisions to a very small size.

The Bhoodan and Gramdan Movements

- Vinoba Bhave, a disciple of Mahatma Gandhi, noticed the problems faced by the landless harijans in Pochampalli, Telangana.

- He led the movements in an attempt to bring about a “non-violent revolution” in India’s land reforms programme.

- The movements were about urging the landed classes to voluntarily surrender a part of their land to the landless giving it the name- Bhoodan Movement.

- It began in 1951.

- The movements were about urging the landed classes to voluntarily surrender a part of their land to the landless giving it the name- Bhoodan Movement.

- In response to the appeal by Vinoba Bhave, some land owning class agreed to voluntary donation of their some part of land.

- The Central and State governments had provided the necessary assistance to Vinoba Bhave.

- Later, the Bhoodan gave way to the Gramdan movement which began in 1952.

- The objective of the Gramdan movement was to persuade landowners and leaseholders in each village to renounce their land rights and all the lands would become the property of a village association for an egalitarian redistribution and joint cultivation.

- Under this movement, a village was declared as Gramdan when at least 75% of its residents with 51% of the land signified their approval in writing for Gramdan.

- The first village to come under Gramdan was Magroth, Haripur, Uttar Pradesh.

- The objective of the Gramdan movement was to persuade landowners and leaseholders in each village to renounce their land rights and all the lands would become the property of a village association for an egalitarian redistribution and joint cultivation.

Successes of the Movement:

- The movement was the first post independence movement that sought to bring social transformation through a movement and not through government legislation.

- It created a moral ambience that put pressure on the big landlords.

- It also stimulated the political activity among the peasants and landless, providing a fertile ground for political propaganda to organise peasants.

Drawbacks:

- The land donated was mostly those which were unfertile or under litigation as a result although large areas of land was collected but little was distributed among the landless.

- Gramdan movement was started in villages where class differentiation had not emerged, there was little difference in landholdings ownership, mainly in tribal areas.

- But it was not successful in areas where there was disparity in landholdings.

- Further, the movement failed to realize its revolutionary potential.

Result:

- The movements received widespread political patronage.

- The movements reached their peak around 1969.

- Several state governments passed laws aimed at Gramdan and Bhoodan.

- But after 1969 Gramdan and Bhoodan lost its importance due to the shift from being a purely voluntary movement to a government supported programme.

- In 1967, after the withdrawal of Vinoba Bhave from the movement, it lost its mass base.

Way Forward

- It has now been argued by the NITI Aayog and some sections of industry that land leasing should be adopted on a large scale to enable landholders with unviable holdings to lease out land for investment, thereby enabling greater income and employment generation in rural areas.

- This cause would be facilitated by the consolidation of landholdings.

- Modern land reforms measures such as land record digitisation must be accomplished at the earliest.

Conclusion

- The pace of implementation of land reform measures has been slow. The objective of social justice has, however, been achieved to a considerable degree.

- Land reform has a great role in the rural agrarian economy that is dominated by land and agriculture. New and innovative land reform measures should be adopted with new vigour to eradicate rural poverty.