Promise and Perils of Legalizing MSP | 03 Dec 2024

This editorial is based on “Unrest over minimum support prices” which was published in The Financial Express on 28/11/2024. The article brings into picture the growing agrarian distress as farmers demand a legal guarantee for MSPs to counter declining incomes and rising risks. It highlights the need for alternatives like deficiency payments and direct income support to ensure sustainability and food security.

For Prelims: Minimum support prices, Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices , Wheat, Shanta Kumar Committee, FRP for sugarcane, WTO's Peace Clause, Agricultural Produce Market Committee, e-NAM, Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana, Zero Budget Natural Farming.

For Mains: Arguments in Favour and Against Legalising MSP, Measures to Strengthen the MSP System in India

Agrarian distress in India remains a pressing issue, with farmers demanding a legal guarantee for minimum support prices (MSPs) for 23 crops to address their declining incomes and rising risks from climate change and high input costs. The fiscal and inflationary implications of a legally mandated MSP regime make it infeasible, prompting calls for alternatives such as deficiency price payments (DPPs) or direct income support. Addressing these demands requires balancing farmers’ incomes with sustainable agricultural practices and food security imperatives.

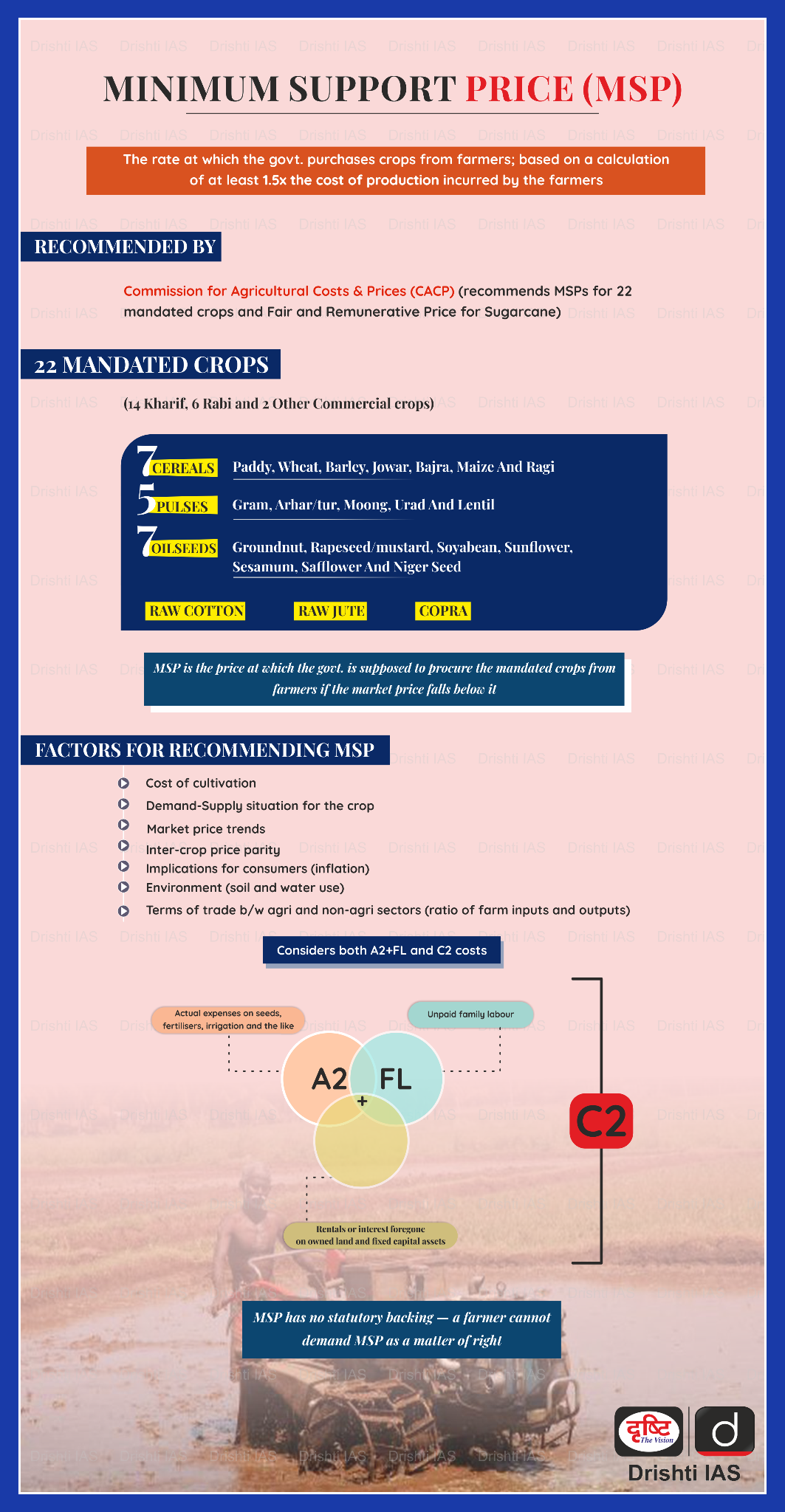

What is the Minimum Support Price?

- MSP: The Minimum Support Price (MSP) system was introduced in 1965 with the establishment of the Agricultural Prices Commission (APC), later renamed the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP).

- This system was designed to intervene in the market to safeguard national food security and protect farmers from significant price drops.

- MSP Calculation: The CACP calculates three categories of production costs for each crop, considering both state-level and national averages:

- A2: This includes all direct costs incurred by the farmer, such as expenses for seeds, fertilizers, pesticides, hired labor, leased land, fuel, irrigation, etc.

- A2+FL: This category adds the estimated value of unpaid family labor to the A2 costs.

- C2: This is a more comprehensive cost calculation, incorporating the cost of owned land, rental, and interest on fixed capital assets, in addition to A2+FL.

- The government asserts that MSP is set at least 1.5 times the all-India weighted average Cost of Production (CoP), but this is calculated based on 1.5 times the A2+FL cost.

- Crops Covered under MSP: MSP supports farmers by guaranteeing a pre-determined price for 23 mandated crops. Additional MSPs are fixed for Toria (based on rapeseed & mustard) and de-husked coconut (based on copra).

What are the Arguments in Favour of Legalising MSP?

- Protecting Farmers Against Market Volatility: Legalizing MSP ensures farmers receive fair compensation despite unpredictable price fluctuations in open markets, safeguarding them from losses caused by surplus production or global trade dynamics.

- For example, in 2024, tomato farmers in Andhra Pradesh faced distress sales due to a price crash, with legal MSP, such disparities can be avoided.

- More than 85% farmers are either small or marginal with average land holding of just about 0.36 ha, highly vulnerable to price volatility.

- Promoting Regional and Crop Equity: Legalizing MSP can address regional disparities by ensuring fair remuneration for farmers in underrepresented states and promoting cultivation of non-cereal crops like pulses and oilseeds.

- Currently, procurement is skewed towards Punjab and Haryana, leaving states like Bihar and Odisha marginalized.

- For example, 80% of the wheat procured in 2021-22 was from the three states of Punjab, Madhya Pradesh and Haryana. Legalizing MSP would help reduce this disparity by ensuring equitable procurement across all regions.

- Mitigating Rural Distress and Farmer Self-harm: In the NCRB data released in December, 2023, it was reported that 6,083 agricultural labourers passed away in 2022 as a result of taking their own lives.

- Legal MSP can alleviate rural distress by ensuring farmers a predictable income, reducing dependence on credit and lowering the incidence of farmer self-harm.

- Encouraging Agricultural Investments: With assured returns through legalized MSP, farmers would feel incentivized to invest in better seeds, technologies, and sustainable practices.

- For example, FRP for sugarcane (8% higher in 2024-25 than 2023-24 price) ensured profitability, encouraging investment in inputs and increasing productivity.

- Reducing Exploitation by Middlemen: The Shanta Kumar Committee's 2015 report reveals that just 6% of farmers benefit from the Minimum Support Price, meaning that 94% of farmers do not gain the intended advantages of the MSP.

- A legalized MSP can bypass the exploitative practices of intermediaries who dominate agricultural markets.

- Tackling Climate-Driven Agricultural Risks: With climate change increasing weather unpredictability, legalized MSP ensures income stability for farmers affected by crop losses.

- For example, unseasonal rains, hailstorms, and strong winds have damaged over 5.23 lakh hectares of wheat crops in Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, and Madhya Pradesh in 2023, causing harvest challenges and concerns over significant yield losses.

- Strengthening India’s Agricultural Exports: A legal MSP framework provides a predictable pricing regime, helping align production with global demand and boosting exports.

- For instance, In 2022–23, the country's rice exports totaled $11 billion, with basmati rice experiencing a notable 21.9% growth in export value for 2023–24.

- Such measures can reduce trade imbalances and enhance India’s global agricultural competitiveness.

What are the Arguments Against Legalising MSP?

- Fiscal Burden on the Exchequer: Implementing a legally mandated MSP across all eligible crops would significantly strain the government's finances.

- CRISIL Market Intelligence & Analytics estimated that the "real cost" of MSP guarantee for the government would be approximately ₹21,000 crore in the Agriculture Marketing Year (MY) 2023.

- This figure represents a substantial portion of India's total budgeted expenditure, raising concerns about fiscal sustainability.

- Implementation Challenges in Unregulated Markets: A significant portion of agricultural transactions occur outside regulated mandis, complicating the enforcement of a legal MSP.

- In Maharashtra, a 2018 attempt to mandate MSP led to trader boycotts. This highlights the practical difficulties in monitoring and enforcing MSP across diverse and informal market channels.

- Inflationary Pressures: Mandating higher crop prices through legal MSP can contribute to food inflation, adversely affecting consumers, especially the economically vulnerable.

- Economists note that a 1% increase in MSP can lead to a 15 basis points rise in inflation, impacting overall economic stability.

- International Trade Implications: Legalizing MSP may conflict with World Trade Organization (WTO) norms on agricultural subsidies, potentially leading to trade disputes.

- India has previously invoked the WTO's Peace Clause for exceeding subsidy limits on rice, indicating the delicate balance required in subsidy policies to avoid international repercussions.

- Risk of Inefficient Resource Allocation: Legal MSP could incentivize farmers to grow MSP-backed crops like rice and wheat disproportionately, exacerbating issues like groundwater depletion and soil degradation.

- Punjab and Haryana have lost a staggering 64.6 billion cubic metres of groundwater in the 17 years between 2003 to 2020. Legal MSP risks deepening this unsustainable resource usage.

- Negative Environmental Consequences: MSP-supported monoculture, particularly of water-intensive crops like paddy and sugarcane, has been linked to biodiversity loss, soil salinity, and greenhouse gas emissions.

- For example, sugarcane in Maharashtra consumes 70% of the state’s irrigation water. Legal MSP may inadvertently exacerbate such environmental issues.

- Overburdening Government Procurement Mechanisms: Legalizing MSP would necessitate universal procurement, potentially overwhelming storage capacities and distribution systems.

- India's food grain production stands at 311 MMT, but the storage capacity is only 145 MMT, resulting in a shortfall of 166 MMT. While other countries have 131% surplus storage capacity, India faces a 47% shortfall.

- Increasing procurement through legal MSP would further strain these already stressed systems.

- Lack of Complimentary Market Reforms: Legal MSP would focus on price guarantees without addressing deeper structural issues in agricultural markets, such as inefficient Agricultural Produce Market Committee(APMC) systems and lack of direct farmer-market linkages.

- APMC mandis are concentrated in certain regions, leaving vast areas without access to regulated markets.

- For instance, India has only one mandi for every 496 square kilometers, far below the National Commission on Farmers' recommendation of one mandi for every 80 square kilometers.

What Measures can be Adopted to Strengthen the MSP System in India?

- Implement a Deficiency Price Payment (DPP) System: The government can compensate farmers for the gap between MSP and market prices through a direct transfer mechanism.

- This reduces fiscal burden by avoiding large-scale procurement while ensuring farmers receive fair compensation.

- States like Madhya Pradesh have experimented with the Bhavantar Bhugtan Yojana, demonstrating its feasibility.

- Implementing DPP nationwide, combined with digital platforms for real-time price tracking, can bridge income gaps effectively.

- Promote Decentralized Procurement Mechanisms: Decentralizing procurement to involve state governments and local self-help groups ensures wider geographical coverage and equitable benefit distribution.

- For example, Chhattisgarh’s decentralized procurement of paddy has proven successful in involving local farmers.

- Decentralization can address regional disparities in procurement while reducing logistical pressures on central storage systems.

- Enhancing APMCs: Modernizing Agricultural Produce Market Committees (APMCs) and integrating them with e-NAM (National Agriculture Market) can create transparent and competitive marketplaces, building upon Gujarat’s APMC reforms and Model APMC Act.

- Increasing the number of APMC markets, improving their efficiency, and providing farmers with digital literacy can empower them to negotiate better prices while reducing middlemen exploitation.

- Encourage Crop Diversification Through MSP Incentives: Higher MSPs for pulses, oilseeds, and millets can shift focus from water-intensive crops like rice and sugarcane.

- This aligns with sustainable agriculture goals, reducing environmental degradation.

- The success of government programs promoting millets in the International Year of Millets (2023) highlights the potential of tailored MSPs to incentivize diversification and support agroecology.

- Adopt Climate-Resilient Support Mechanisms: Introduce climate-smart MSPs that factor in risks like erratic rainfall and pest attacks.

- The system can link MSP determination with insurance schemes such as PMFBY (Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana) to create a safety net for climate-vulnerable farmers.

- Establishing localized MSP for drought-resistant crops can also reduce the economic impact of climate-related crop failures.

- Strengthen Farmer Producer Organizations: FPOs can play a critical role in pooling resources and negotiating better market access for small and marginal farmers.

- Linking FPOs with MSP operations ensures collective bargaining power, reduces dependence on intermediaries, and facilitates direct market linkages.

- This approach also aligns with the government’s objective of creating 10,000 FPOs under the Atmanirbhar Bharat initiative.

- Integrate Sustainable Practices with MSP: Make MSP conditional on adherence to sustainable agricultural practices like reduced chemical fertilizer use, crop rotation, and organic farming.

- Incentivizing farmers through a "green MSP" linked to sustainability metrics can address environmental concerns.

- Pilot programs like Zero Budget Natural Farming (ZBNF) in Andhra Pradesh can guide nationwide implementation.

- Expand Warehousing and Storage Capacities: Investing in modern warehousing infrastructure through public-private partnerships can address the significant storage deficit.

- Expanding cold storage chains for perishable crops ensures MSP coverage for horticultural products.

- Improved storage facilities minimize post-harvest losses and ensure better price realization for farmers.

- Integrate MSP with Export Strategies: Align MSP policies with export-oriented production to enhance global competitiveness.

- Encouraging crops like basmati rice and certain oilseeds, backed by MSP and quality certification, can boost agricultural exports.

- This reduces the fiscal burden of domestic procurement and strengthens India's agricultural trade balance.

- Develop Crop-Specific Processing and Value Addition Units: Link MSP-procured crops to agro-processing industries to enhance value addition and minimize wastage.

- For instance, setting up pulse-processing units in key production areas can generate income for farmers and create rural employment.

- This aligns with schemes like PM Kisan Sampada Yojana, which seeks to strengthen post-harvest infrastructure.

- Incorporate Technological Solutions for Real-Time Price Discovery: Leverage Artificial Intelligence (AI) and blockchain technologies to develop platforms that monitor real-time market prices and provide transparency in MSP implementation.

- These platforms can also help predict price trends, aiding farmers in better crop selection and reducing market exploitation.

- Provide Graded MSP for Quality Produce: Introduce a tiered MSP structure based on crop quality, encouraging farmers to invest in better seeds and post-harvest handling.

- For example, higher MSP for premium-grade grains can incentivize the production of export-quality commodities.

- Expand Direct Benefit Transfers (DBT) to Replace Input Subsidies: Streamlining input subsidies (fertilizers, seeds) into direct cash transfers allows farmers to invest flexibly in production while reducing government expenditure.

- This model, successfully piloted in Telangana’s Rythu Bandhu scheme, can be scaled up nationwide and linked with MSP guarantees to ensure income support.

- Enhance Monitoring and Grievance Redress Mechanisms: Establish dedicated MSP monitoring committees to oversee implementation, address farmer grievances, and ensure timely payments.

- A robust system for agricultural markets can bring accountability and transparency to the process.

- Promote MSP for Emerging Agricultural Sectors: Expand MSP coverage to include new-age crops like quinoa, flaxseed, and medicinal plants, reflecting changing consumer demand and export potential.

- This diversifies farmers’ income sources and aligns India’s agricultural strategy with global trends.

Conclusion:

The debate on legalizing MSP highlights the complex interplay between farmer welfare, fiscal sustainability, and food security. A balanced approach, including DPPs, decentralized procurement, market reforms, and sustainable practices, is crucial to ensure a win-win situation for both farmers and the government. By addressing the underlying issues of market imperfections, climate risks, and low incomes, India can create a robust and sustainable agricultural system that benefits all stakeholders.

|

Drishti Mains Question: Critically examine the potential benefits and challenges of legalizing MSP in the context of India's agricultural sector, and suggest measures to ensure its effective implementation |

UPSC Civil Services Examination Previous Year Question (PYQ)

Prelims

Q. Consider the following statements: (2020)

- In the case of all cereals, pulses, and oil seeds, the procurement at Minimum Support price (MSP) is unlimited in any State/UT of India.

- In the case of cereals and pulses, the MSP is fixed in any State/UT at a level to which the market price will never rise.

Which of the statements given above is/are correct?

(a) 1 only

(b) 2 only

(c) Both 1 and 2

(d) Neither 1 nor 2

Ans: (d)

Q. Consider the following statements: (2023)

- The Government of India provides Minimum Support Price for niger (Guizotia abyssinica) seeds.

- Niger is cultivated as a Kharif crop.

- Some tribal people in India use niger seed oil for cooking.

How many of the above statements are correct?

(a) Only one

(b) Only two

(c) All three

(d) None

Ans: (c)

Mains

Q. What do you mean by Minimum Support Price (MSP)? How will MSP rescue the farmers from the low income trap? (2018)