Social Justice

Higher Education In India

- 06 Apr 2020

- 9 min read

This article is based on “The Idea of a University in India” which was published in Economic and Political Weekly on 04/04/2020. It talks about challenges faced by higher education in India.

In India, universities were established as early as in 1857 (Calcutta, Bombay and Madras Universities were all established in the same year). These universities didn't emerge to keep pace with the growth of knowledge, but to fulfill the interests handpicked by the colonial rulers.

Universities in independent India were based on the idea of state welfarism. It sought to grant equal opportunities to its citizens in accessing national resources, made university education not only accessible, but also converted it into a mass product.

Thus, the massification of higher education went on with the increase in the number of universities along with enrolments. It got further aggravated after Liberalisation, Privatisation and Globalisation (LPG reforms) in 1990-91.

However, massification of higher education has to deal with multiple challenges of accessibility, equity and quality.

Higher Education In India

- Higher education follows a trajectory in which it will transform from being the privilege of a few (elite phenomenon), to a resource of the majority, more as a right (mass phenomena), and finally a collective obligation (a universal phenomenon).

- Elite level implies a national enrolment ratio of (up to) 15%, the mass level ranges between 15% and 50%, and surpassing 50% enrolment is indicative of the universalisation of higher education.

- Higher education in India by these standards stands out to be in a stage of initial massification with 26.3% Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER) in 2018-19.

- This massification of higher education happens through:

- Changing policy perspectives (that guarantee rapid expansion of higher education institutions and enrolments).

- Growing impact of democratic forces in politics (democratisation of higher education).

- Strong voices from the civil society (endorsing accessibility and spread of higher education).

Note:

- As per the 2018 All India Survey of Higher Education data, there are 903 universities, 37.98% of them are privately managed.

- The GER for the male population is 26.3%, and for female population it is 25.4% (Department of Higher Education

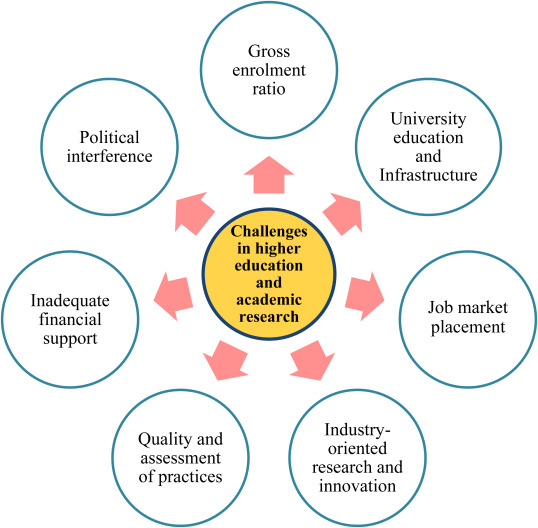

Challenges faced by Higher Education In India

Enterprise Model

- According to the National Knowledge Commission (NKC) Report (2009), the higher education institutions have been primarily visualised as an application-oriented enterprise.

- These are directed towards translating scientific knowledge into innovation-oriented application, and thereby making the entire process a commercially exploitable property.

- India’s higher educational institutions are not even to inculcate scientific and innovation-led outlook amongst the students.

- Pedagogy and assessment are focused on input and rote learning and there are neglected skills, including critical thinking, analytical reasoning, problem-solving and collaborative working.

Passive and Catching-up Mode

- Scholars have identified two different modes of massification at the global level, namely an active mode, and a passive and catching-up mode.

- The “active mode” is exemplified by developed countries, where the massification of higher education took place more as a natural outcome of economic development.

- The “passive and catching-up” mode can be experienced in developing countries where the massification of higher education is often pushed as a leap forward by the government, while the level of economic development might not have increased adequately.

- Education systems based on passive and catching-up mode may suffer from issues like lack of adequate skills & jobs and underemployment.

- India is among many countries where the “passive and catching-up” mode of massification is largely in operation.

Problem of Scarcity

- Consequently, countries characterised by the “passive and catching-up” mode of massification have to rely more on private rather than government-aided institutions for obvious economic reasons.

- The heavy dependence on privately-managed institutes as a means of massification has often resulted in debatable consequences, to the extent of perpetuating inequality in accessing higher education.

Two-boxed System

- In India there are separate research institutes and universities.

- The separation in higher education between teaching institutions and research institutions post-independence has caused much harm, as most universities and colleges in the country today conduct very little research.

- According to draft National Education Policy 2019, the proportion of GDP devoted to research and innovation in India has dropped over the past decade, from 0.84% of GDP in 2008 to 0.69% in 2014 -- which is substantially lower than the percentages for Israel (4.3%), South Korea (4.2%) and the U.S. (2.8 %).

- Also, there are very few opportunities for interdisciplinary learning.

Other Issues

- One of the greatest challenges faced by higher education in India is the chronic shortage of teaching faculty.

- Nearly 30 to 40% of faculty positions are vacant.

- Further, most faculty lack quality in teaching, research and training.

- None of the universities and institutions from India are in the list of top hundred universities in the world.

- This resulted in graduates with low employability, a common feature of higher education in India.

- An ineffective quality assurance system and lack of autonomy and accountability by institutions to the state and central government, students and other stakeholders.

Way Forward

The role of higher education in shaping the students’ future depends on a transparent, progressive, socially responsible and ethical educational system. In this context, the draft National Education Policy 2019 calls for fundamentally restructuring the country's higher education system.

- The policy seeks to boost India's research capacity, doubling the gross enrollment rate from 25 to 50% by 2035, and substantially increasing expenditures on public education, which currently account for 10% of all government spending.

- It also revives a long-stalled idea of inviting top-ranked foreign universities to operate in India and suggests legislation will be introduced to this effect.

- The policy calls for all higher education institutions to “evolve” into one of three types of multidisciplinary institutions: Research universities, teaching universities and colleges.

- It also calls for building research capacities at all institutions and the establishment of a National Research Foundation.

- The draft policy includes a wide range of other proposals:

- Adopting a more liberal arts-oriented form of undergraduate education.

- Moving away from rote learning in curriculum and pedagogy.

- Improving faculty autonomy and developing a robust and merit-based tenure track, promotion and salary structure.

- Increasing institutional autonomy, with institutions to be governed by independent boards.

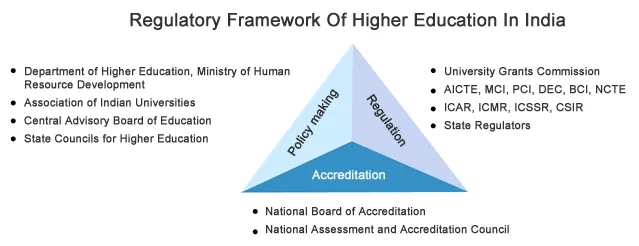

Revamping the regulatory system to only have one regulator for all of higher education.

Though, the draft education policy seems very promising, the real challenge would be the proper implementation of this.

|

Drishti Mains Question Discuss the challenges and solutions pertaining to the higher education sector In India. |