Indian History

Republics in Ancient India

- 06 Oct 2021

- 5 min read

Why in News

Recently, while addressing the United Nations General Assembly, the Prime Minister made an important historical point that India is not just the world’s largest democracy, but also the Mother of Democracy.

- There is evidence of the existence of proto forms of democracy and republicanism in ancient India.

Key Points

- Vedic Governance: The Vedas describe at least two forms of republican governance:

- Monarchy: The first would consist of elected kings. This has always been seen as an early form of democracy.

- Republics: The second form is that of rule without a monarch, with power vested in a council or sabha.

- The membership of such sabhas was not always determined by birth, but they often comprised people who had distinguished themselves by their actions.

- There is even a hint of the modern bicameral system of legislatures, with the sabha often sharing power with the samiti, which was made up of common people.

- The vidhaata, or the assembly of people for debating policy, military matters and important issues impacting all, has been mentioned more than a hundred times in the Rig Veda. Both women and men took part in these deliberations.

- Mahabharata:

- In Chapter 107/108 of Mahabharata’s Shanti Parva, there is a detailed narration about the features of republics (called ganas) in India.

- It states that when there is unity among the people of a republic that republic becomes powerful and its people become prosperous and they are destroyed only by internal conflicts between the people.

- It shows that in ancient India there were not only kingdoms (like Hastinapur and Indraprastha) but also regions where there was no king but a republic.

- In Chapter 107/108 of Mahabharata’s Shanti Parva, there is a detailed narration about the features of republics (called ganas) in India.

- Buddhist Canons:

- The Buddhist Canon, both in Sanskrit (in which much of Mahayana Buddhist literature was written) and in Pali (in which much of Hinayana literature was written) has extensive reference to republics in India, e.g. the Lichchavi city of Vaishali.

- It also describes in detail Vaishali’s rivalry with neighbouring Magadha, which was a monarchy. Had the Lichchavis won, the trajectory of governance may well have been non-monarchical in the Subcontinent.

- The Mahanibbana Sutta (Pali Buddhist work) and the Avadaana Shatak (a Sanskrit Buddhist text of the second century A.D) also mention that certain areas were under a republican form of government.

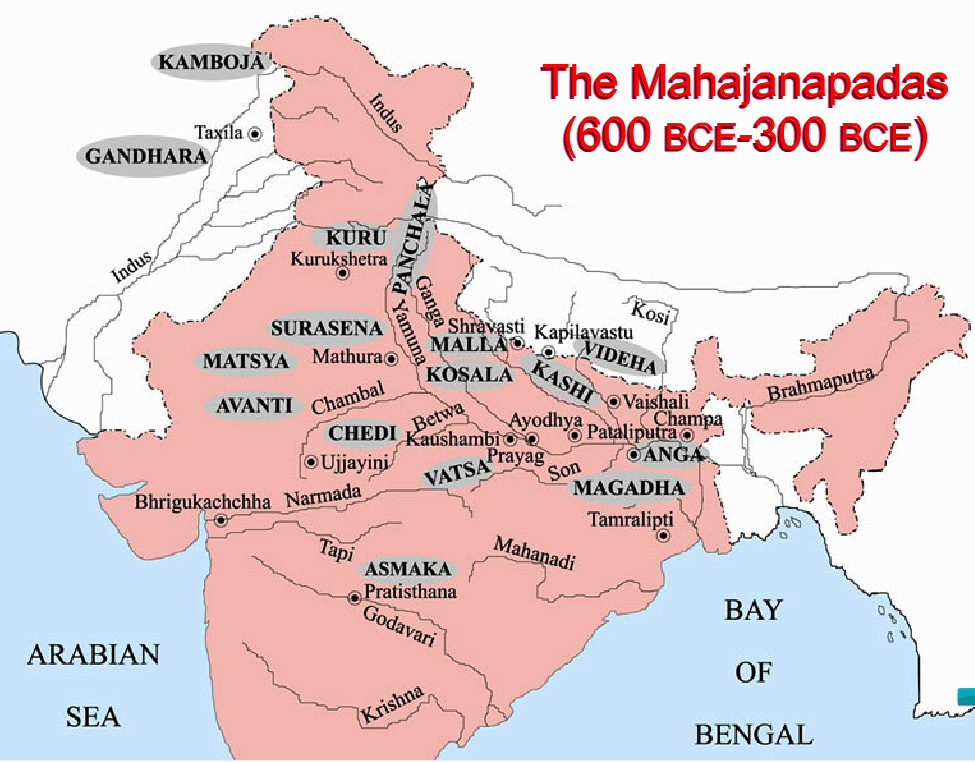

- Buddhist and Jain texts list 16 powerful states or mahajanapadas of the time.

- The Buddhist Canon, both in Sanskrit (in which much of Mahayana Buddhist literature was written) and in Pali (in which much of Hinayana literature was written) has extensive reference to republics in India, e.g. the Lichchavi city of Vaishali.

- Greek Records:

- The Greek historian Diodorus Siculus writes that at the time of Alexander’s invasion (in 326 B.C.), most cities in North West India had democratic forms of government (though some areas were under kings, e.g. Ambhi and Porus) and this is also mentioned by the historian Arian.

- Alexander’s army faced its fiercest resistance from the armies of these republics, e.g. the Mallas, and gained victory only after suffering huge casualties.

- The Greek historian Diodorus Siculus writes that at the time of Alexander’s invasion (in 326 B.C.), most cities in North West India had democratic forms of government (though some areas were under kings, e.g. Ambhi and Porus) and this is also mentioned by the historian Arian.

- Kautilya’s Arthashastra:

- Other sources appear in the Ashtadhyayi of Panini, the Arthashastra of Kautilya, etc.

- Elements of State by Kautilya: Any state is thought of as composed of seven elements. The first three are swami or the king, amatya or the ministers (administration) and janapada or the people.

- The king must function on the advice of the amatyas for the good of the people.

- The ministers are appointed from amongst the people (the Arthashastra also mentions entrance tests).

- As per the Arthashastra, in the happiness and benefit of his people lies the happiness and benefit of the King.