Issues in WTO’s Dispute Resolution Mechanism | 20 May 2019

The World Trade Organization’s (WTO) dispute settlement mechanism is going through a crisis. The body is struggling to appoint new members to its understaffed Appellate Body that hears appeals in trade.

Over 20 developing countries met in New Delhi on 13-14 May 2019 to discuss the ways to prevent the WTO’s dispute resolution system from collapsing due to the logjam in the appointments.

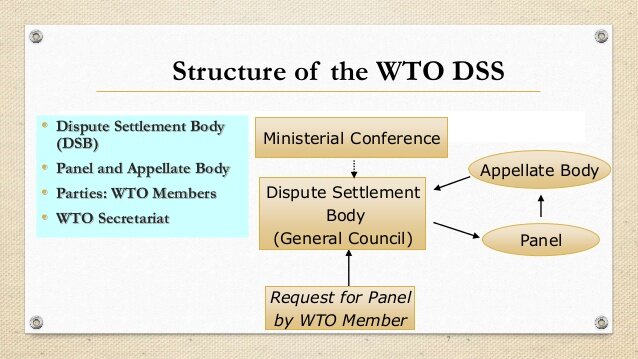

WTO’s Appellate Body

- The Appellate Body, set up in 1995, is a standing committee of seven members that presides over appeals against judgments passed in trade-related disputes brought by WTO members.

- Countries involved in a dispute over measures purported to break a WTO agreement or obligation can approach the Appellate Body if they feel the report of the panel set up to examine the issue needs to be reviewed on points of law.

- However, existing evidence is not re-examined but legal interpretations are reviewed.

- The Appellate Body can uphold, modify, or reverse the legal findings of the panel that heard the dispute. Countries on either or both sides of the dispute can appeal.

- The Appellate Body has so far issued 152 reports. The reports, once adopted by the WTO’s dispute settlement body, are final and binding on the parties.

Issues in WTO’s Appellate Body

- Over the last few years, the membership of the body has shriveled to just three persons instead of the required seven.

- This is because the United States, which believes the WTO is biased against it, has been blocking appointments of new members and reappointments of some members who have completed their four-year tenure.

- Two members will complete their tenures in December 2019, leaving the body with just one member.

- At least three people are required to preside over an appeal, and if new members are not appointed to replace the two retiring ones, the body will cease to be relevant.

- The understaffed appeals body has been unable to stick to its 3 month deadline for appeals filed in the last few years, and the backlog of cases has prevented it from initiating proceedings in appeals that have been filed in the last year.

India’s Disputes in WTO

- India has so far been a direct participant in 54 disputes, and has been involved in 158 as a third party.

- In February 2019, the body said it would be unable to staff an appeal in a dispute between Japan and India over certain safeguard measures that India had imposed on imports of iron and steel products.

NOTE: The dispute panel (India and Japan) had found that India had acted “inconsistently” with some WTO agreements, and India had notified the Dispute Settlement Body of its decision to appeal certain issues of law and legal interpretations in December 2018.

Implications

- With the Appellate Body unable to review new applications, there is already great uncertainty over the WTO’s dispute settlement process.

- If the body is declared non-functional in December, countries may be compelled to implement rulings by the panel even if they feel that gross errors have been committed.

- Countries may refuse to comply with the order of the panel on the ground that it has no avenue for appeal. It will run the risk of facing arbitration proceedings initiated by the other party in the dispute.

- This also does not bode well for India, which is facing a rising number of dispute cases, especially on agricultural products.

- In the backdrop of rising trade tension between the US and China, the overall weakening of the WTO framework could have the effect of undoing over two decades of efforts to avoid protectionism in global trade.

Way Forward

- Usually, new appointments to the Appellate Body are made by a consensus of WTO members, but there is also a provision for voting where a consensus is not possible.

- The group of 17 least developed and developing countries, including India, that have committed to working together to end the impasse at the Appellate Body can submit or support a proposal to this effect, and try to get new members on the Appellate Body by a majority vote.

- But, this may be an option of the last resort, as all countries fear unilateral measures by the US as a consequence of directly opposing its veto.