Antarctica’s Doomsday Glacier | 13 Apr 2021

Why in News

Researchers from Sweden’s University of Gothenburg have been able to obtain data from underneath Thwaites Glacier, also known as the 'Doomsday Glacier'.

- They find that the supply of warm water to the glacier is larger than previously thought, triggering concerns of faster melting and accelerating ice flow.

Key Points

- Doomsday Glacier:

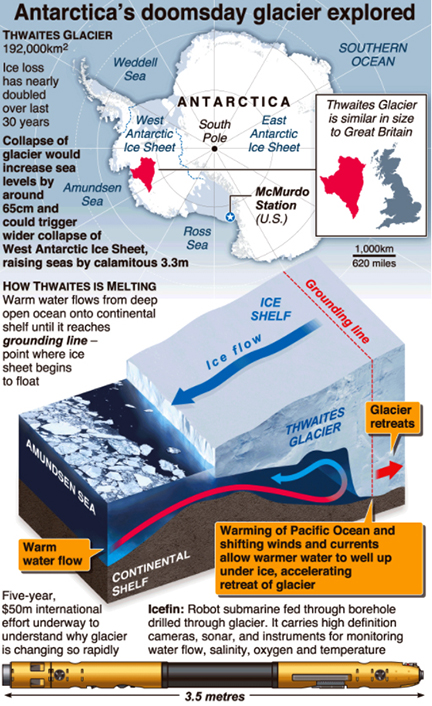

- Called the Thwaites Glacier, it is 120 km wide at its broadest, fast-moving, and melting fast over the years.

- Because of its size (1.9 lakh square km), it contains enough water to raise the world sea level by more than half a metre.

- Studies have found the amount of ice flowing out of it has nearly doubled over the past 30 years.

- Today, Thwaites’s melting already contributes 4% to global sea level rise each year.

- It is estimated that it would collapse into the sea in 200-900 years.

- Thwaites is important for Antarctica as it slows the ice behind it from freely flowing into the ocean.

- Because of the risk it faces, and poses, Thwaites is often called the Doomsday Glacier (Doomsday meaning warning or threat, something that can cause destruction).

- Previous Studies:

- Hole in the Glacier: A 2019 study had discovered a fast-growing cavity in the glacier, sized roughly two-thirds the area of Manhattan.

- The size of a cavity under a glacier plays an important role in melting. As more heat and water get under the glacier, it melts faster.

- Detection of Warm Water at Grounding Line:

- About: In 2020, researchers from New York University (NYU) detected warm water at a vital point below the glacier. In the NYU study, scientists dug a 600-m-deep and 35-cm-wide access hole, and deployed an ocean-sensing device called Icefin to measure the waters moving below the glacier’s surface.

- Findings:

- The NYU study reported water at just two degrees above freezing point at Thwaites’s “grounding zone” or “grounding line”.

- The grounding line is the place below a glacier at which the ice transitions between resting fully on bedrock and floating on the ocean as an ice shelf. The location of the line is a pointer to the rate of retreat of a glacier.

- When glaciers melt and lose weight, they float off the land where they used to be situated. When this happens, the grounding line retreats. That exposes more of a glacier’s underside to seawater, increasing the likelihood it will melt faster.

- This results in the glacier speeding up, stretching out, and thinning, causing the grounding line to retreat ever further.

- Hole in the Glacier: A 2019 study had discovered a fast-growing cavity in the glacier, sized roughly two-thirds the area of Manhattan.

- Findings from Sweden’s Gothenburg Study (New Study):

- About: Sweden’s Gothenburg study used an uncrewed submarine to go under the Thwaites glacier front to make observations.

- The submersible called “Ran” measured among other things the strength, temperature, salinity and oxygen content of the ocean currents that go under the glacier.

- Using the results, the researchers have been able to map the ocean currents that flow below Thwaites’s floating part.

- Findings: The researchers have been able to identify three inflows of warm water, among whom the damaging effects of one had been underestimated in the past.

- The researchers discovered that there is a deep connection to the east through which deep water flows from Pine Island Bay, a connection that was previously thought to be blocked by an underwater ridge.

- Pine Island Bay is a drainage system of West Antarctica.

- The study also looked at heat transport in one of the three channels which brings warm water towards the glacier from the north.

- They found that there were distinct paths that water takes in and out of the ice shelf cavity, influenced by the geometry of the ocean floor.

- The researchers discovered that there is a deep connection to the east through which deep water flows from Pine Island Bay, a connection that was previously thought to be blocked by an underwater ridge.

- About: Sweden’s Gothenburg study used an uncrewed submarine to go under the Thwaites glacier front to make observations.

Way Forward

- The study shows that warm water is approaching the pinning points of the glacier from all sides, impacting these locations where the ice is connected to the seabed and where the ice sheet finds stability. This has the potential to make things worse for Thwaites, whose ice shelf is already retreating.

- For the first time, data is being collected that is necessary to model the dynamics of Thwaites glacier. This data will help better calculate ice melting in the future.

- With the help of new technology, models can be improved and the great uncertainty that now prevails around global sea level variations can be reduced.