Safeguarding the Autonomy of Tribunals | 25 Jul 2020

This article is based on “Safeguarding the autonomy of tribunals” published in The Hindustan Times on 23/07/2020. It evaluates the new rules promulgated by the centre pertaining to the functioning of the tribunals.

Recently, the Union Ministry of Finance framed a new set of rules called the Tribunal, Appellate Tribunal, and other Authorities (Qualifications, Experience and other Conditions of Service of Members) Rules, 2020 that prescribe uniform norms for the appointment and service conditions of members to various tribunals.

The new rules have been framed by the government as the previous Rules of 2017 were struck down by the Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court in November 2019 in the case Rojer Mathew vs South Indian Bank.

However, the new rules carry out only cosmetic changes and some of the provisions contravene the spirit of law laid down by the Supreme Court (SC) on matters related to tribunals.

Issues With the New Rules

- Conflict of Interest: The new rules do not remove the control of parent administrative ministries (ministries against which the tribunals have to pass orders) over tribunals.

- For example, the tribunals such as the Armed Forces Tribunal functions under the same ministry which is a party in litigation and the ministry also wields rule-making powers and controls finances, infrastructure and manpower in the tribunal.

- This is against the spirit of Natural Justice.

- Rules Diluting Judicial Independence: The selection committee under the new rules can function even in absence of any judicial member, meaning that a committee entirely (or majorly) comprising officers of the executive can select members of tribunals.

- Unwarranted Influence of Executive: The new rules also ensure that the secretary of the ministry against which the tribunal is to pass orders sits on the committee for selecting adjudicating members of the same tribunal.

- This system was termed as “mockery of the Constitution” by SC in Madras Bar Association case, 2014.

- Affecting Independence of Members: The new rules provide for a retirement age of 65 years even for former judges who retire at 62 from the high courts (HCs), which gives them at best a three-year tenure.

- This is against the minimum five to seven years tenure mandated by SC in the Union of India vs R. Gandhi case, 2010 to ensure continuity.

- Further the bar on employment with the government after retiring from tribunals has been removed. Thus, gravely affecting the independence of members.

- Inconsistent with SC rulings: The new rules contain ambiguous clauses stating that any person with experience in economics, commerce, management, industry and administration can be appointed as a member of certain tribunals.

- This may allow even members with non-judicial/legal background to become chairpersons of tribunals, contrary to SC ruling in the R Gandhi case.

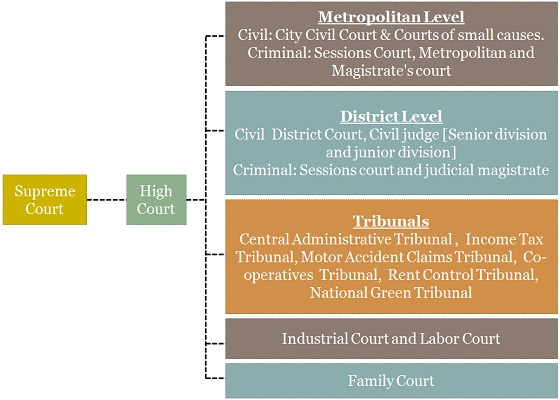

Tribunal

- Tribunal is a quasi-judicial institution that is set up to deal with problems such as resolving administrative or tax-related disputes.

- It performs a number of functions like adjudicating disputes, determining rights between contesting parties, making an administrative decision, reviewing an existing administrative decision and so forth.

- Tribunals were not part of the original constitution, it was incorporated in the Indian Constitution by 42nd Amendment Act, 1976.

- Article 323-A deals with Administrative Tribunals.

- Article 323-B deals with tribunals for other matters.

Way Forward

- Maintain Independence of the Tribunal: Unless steps are taken in compliance with the law laid down by SC for tribunals, neither their independence nor their ability to reduce the burden on the regular judiciary can be guaranteed.

- Tribunals must not be seen as an extension of the executive.

- Separate and Independent Authority for Administration: SC in the cases of L Chandra Kumar (1997), R Gandhi (2010), Madras Bar Association (2014) and Swiss Ribbons (2019) has ruled that tribunals cannot be made to function under the ministries against which they are to pass orders and they must be placed under the law ministry instead.

- Thus, the need to ensure the separate and independent authority for administration of the tribunals is required.

Best Performing: Income Tax Appellate Tribunal

- The Income Tax Appellate Tribunal was created in 1941, at that time it was put under the finance department, but moved to the legislative department (Ministry of Law and Justice) a year later to ensure its independence.

- This arrangement continues till date, and is perhaps the primary reason that it is one of the best-performing tribunals.

- Thus, other tribunals can also be made to function under the law ministry rather than ministries against which they are to pass orders.

- Easing Pressure on Constitutional Courts: Further, in order to remove unnecessary burden on SC and make justice affordable and accessible, it needs to be ensured that the tribunals work efficiently.

- In this context, the high courts, being equally effective constitutional courts, practically should become the last and final court in most litigation after tribunals pass the order.

- Thus, SC can be allowed to focus more on constitutional points of law of general public importance, Centre-state/inter-state disputes or where there is a major conflict between decisions of two or more high courts. “Special Leave to Appeal” may be extended only to really “special” cases.

- These measures will not only provide consistency and stability but also promote judicial discipline in the tribunal as well as the whole judicial system.

Conclusion

It is the need of the hour that the Union government shows enough will to force systemic tribunal reforms. A reform to the tribunals system in India may as well be one of the keys to remedy the age old problem that still cripples the Indian judicial system – the problem of judicial delay and backlog.

In this context, an independent autonomous body such as a National Tribunals Commission (NTC), responsible for oversight as well as administration, can go a long way in remedying issues that plague the functioning of tribunals.

|

Drishti Mains Question “Reform in the tribunals system in India can address the problems that still cripples the Indian judicial system.” Comment. |

This editorial is based on “Dissent, Contempt” which was published in The Times of India on July 24th, 2020. Now watch this on our Youtube Channel.