Indian Polity

Creamy Layer for SCs/STs

This article is based on “Creamy layer principle in SC, ST quota for promotion: judgments, appeals” which was published in The Indian Express on 11/12/2019. It talks about applicability of creamy layer principle to promotions for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes in government jobs.

Recently, the Centre had asked the Supreme Court to refer the question of ‘whether the creamy layer concept should apply or not to the Scheduled Castes (SCs)/Scheduled Tribes (STs) while providing them reservation in promotions’ to a larger Bench reconsidering its earlier pronouncement in M. Nagaraj & Others vs Union of India case (2006).

What is the creamy layer concept?

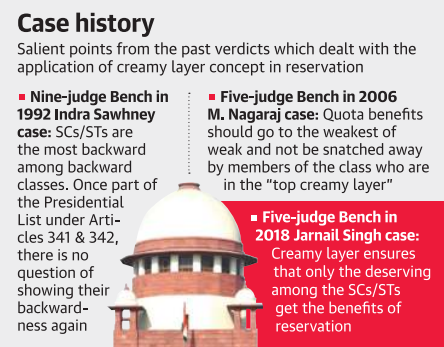

- The expression ‘means-test and creamy layer’ first found its mention in the Supreme Court’s landmark judgment in the Indra Sawhney vs Union of India case of 1992 (also known as Mandal Commission case), that was delivered by a nine-judge Bench on November 16, 1992.

- The creamy layer was then described as- “some members of a backward class who are socially, economically as well as educationally advanced as compared to the rest of the members of that community. They constitute the forward section of that particular backward class and eat up all the benefits of reservations meant for that class, without allowing benefits to reach the truly backward members”.

- The Court also asked the Central government to fix the norms for income, property and status for identifying the creamy layer. In 1993, the creamy layer ceiling was fixed at ₹1 lakh. It was subsequently increased to ₹2.5 lakh (2004), ₹4.5 lakh (2008), ₹6 lakh (2013), and at ₹8 lakh since 2017.

Creamy Layer Chronology

- In 1980, the Mandal Commission report recommended to provide 27% reservation to Other Backward Classes (OBCs) in jobs.

- In 1990, the V P Singh Government declared such reservation of 27% in government jobs for the OBCs.

- In 1991, the Narasimha Rao Government introduced a change in order to give preference to the poorer sections among the OBCs while granting the 27% quota.

- In the Indra Sawhney judgment (1992), the Court upheld the government’s move and proclaimed that the advanced sections among the OBCs (i.e, the creamy layer) must be excluded from the list of beneficiaries of reservation. It also held that the concept of creamy layer must be excluded for SCs & STs.

How was the creamy layer made applicable to SC/ST members?

- In the Nagaraj case (2006) the issue had arisen regarding the validity of the following four Constitutional amendments, claiming that these amendments made by the government were meant to reverse the decisions made by the Court in the Indra Sawhney Case, 1992:

- 77th Constitutional Amendment Act, 1995: The Indra Sawhney verdict had held there would be reservation only in initial appointments and not promotions. But the government through this amendment introduced Article 16(4A) to the Constitution, empowering the state to make provisions for reservation in matters of promotion to SC/ST employees if the state feels they are not adequately represented.

- 81st Constitutional Amendment Act, 2000: It introduced Article 16(4B), which says unfilled SC/ST quota of a particular year, when carried forward to the next year, will be treated separately and not clubbed with the regular vacancies of that year. While the Supreme Court in the Indra Sawhney Case capped the reservation quota at 50%, the government by this amendment ensured that 50% ceiling for these carried forward unfilled posts does not apply.

- 82nd Constitutional Amendment Act, 2000: It inserted a condition at the end of Article 335 that enables the state to make any provision in favour of the members of the SC/STs for relaxation in qualifying marks in any examination or lowering the standards of evaluation, for reservation in matters of promotion to any class or classes of services or posts in connection with the affairs of the Union or of a State.

Constitutional Provision: Article 335 recognises that special measures need to be adopted for considering the claims of SCs and STs to services and posts, in order to bring them at par. It is read as: “The claims of the members of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes shall be taken into consideration, consistently with the maintenance of efficiency of administration, in the making of appointments to services and posts in connection with the affairs of the Union or of a State.”

- 85th Constitutional Amendment Act, 2001: It provided for the reservation in promotion can be applied with ‘consequential seniority’ for the government servants belonging to the SCs and STs with retrospective effect from June 1995.

Key Pronouncements of M. Nagaraj Case (2006)

The Court in this case laid down three conditions for promotion of SCs and STs in public employment:

- Government cannot introduce quota unless it proves that the particular community is backward,

- Inadequately represented (based on quantifiable data), and

- Providing reservation in promotion would not affect the overall efficiency of public administration.

- The five-judges Bench in Nagaraj case although upheld the constitutional validity of all four amendments, but the following two validations by the Supreme Court in this case became the bone of contention:

- First: The Court proclaimed that the State is not bound to make reservation for SC/ST in the matter of promotions. However if they wish to exercise their discretion and make such provision, the State has to collect quantifiable data showing backwardness of the class and inadequacy of representation of that class in public employment in addition to compliance of Article 335.

- Second: Also, it reversed its earlier stance in Mandal case, in which it had excluded the creamy layer concept on SCs/STs (that was applicable on OBCs). The verdict in Nagaraj case made clear that even if the State has compelling reasons (as stated above), the State needs to ensure that its reservation provision does not lead to excessiveness- breaching the ceiling-limit of 50%, or destroying the creamy layer principle, or extending the reservation indefinitely. Therefore, the Court extended the creamy layer principle to SCs and STs too in this verdict.

Current Demand by the Centre

- The Centre asked the Court to review its stance on the above two issues:

- As collecting quantifiable data showing backwardness is contrary to the Mandal case pronouncement where it was held that Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes are the most backward among backward classes. It is, therefore, presumed that once they are added in the Presidential List under Articles 341 and 342 of the Constitution of India, there is no question of proving backwardness of the SCs and STs all over again.

- The said List cannot be altered by anybody except Parliament under Articles 341 and 342- defining who will be considered as SCs or STs in any state or Union Territory.

- And, the creamy layer concept has not been applied in the Indra Sawhney case.

- As collecting quantifiable data showing backwardness is contrary to the Mandal case pronouncement where it was held that Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes are the most backward among backward classes. It is, therefore, presumed that once they are added in the Presidential List under Articles 341 and 342 of the Constitution of India, there is no question of proving backwardness of the SCs and STs all over again.

- The Court clarifying its stance in Jarnail Singh vs Lachhmi Narain Gupta case (2018) refused to refer the above issue to a larger bench.

- However, it invalidated the requirement of collecting quantifiable data by states on the backwardness of SCs and STs while granting quota in promotions as laid down by the Court in Nagaraj verdict, but states need to back it with appropriate data showing the inadequate representation of SCs & STs in the cadre.

- On the creamy layer principle for excluding the well-off amongst the SC/ST communities from availing the benefit, the Court followed the Nagaraj verdict.

- The Court held that socially, educationally, and economically advanced cream of Scheduled Castes/Scheduled Tribes communities must be excluded from the benefits of reservation in government services in order to transfer quota benefits to the weakest of the weaker individuals and not be snatched away by members of the same class who were in the “top creamy layer”.

- The Court also observed that it will not be possible to uplift the weaker sections if only the creamy layer within that class bags all the coveted jobs in the public sector and perpetuate themselves, leaving the rest of the class as backward as they were.

- The government is now asking the Supreme Court to reconsider its verdict in Jarnail Singh case with respect to the applicability of creamy layer principle.

Reservation provides appropriate positive discrimination for the benefit of the socially and educationally backward sections of the society. And the creamy layer concept helps in ensuring that only the genuinely deserving and the most downtrodden members of any particular community get those reservation benefits.

| Drishti Mains Question Briefly discuss the process of the evolution of ‘principle of creamy layer’ in reservations. What are the advantages and challenges associated with it? |