Social Justice

Minimizing the Burden of Hospital Charges

This editorial is based on “Court’s nudge on hospital charges, a reform opportunity” which was published in The Hindu on 30/04/2024. The article examines the soaring healthcare expenses in India and emphasizes that achieving affordable hospital care necessitates health care financing reforms that extend beyond mere price regulations.

For Prelims: Ayushman Bharat, Venture Capital Fund, National Health Profile, Non-communicable diseases (NCDs), Indian Journal of Public Health, National Health Mission, Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (AB-PMJAY), National Medical Commission, PM National Dialysis Programme, Ransomware Attack on AIIMS Delhi, One Health Approach, Public Interest Litigation (PIL), Clinical Establishments (Registration and Regulation) Act, 2010.

For Mains: Reforms needed in India’s Healthcare Sector, Issues Associated with India’s Healthcare Sector, Government Initiatives Related to Healthcare.

The Supreme Court of India, while hearing a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) in February, 2024, directed the central government to find ways to regulate the rates of hospital procedures in the private sector. The trigger for the PIL and directive were the high procedure rates and their large variations across the country in the recent times. The Court highlighted the problem using the procedure costs of cataract surgeries that cost only around Rs. 10,000 in a government set-up and between Rs. 30,000 to Rs. 1,40,000 in private hospitals.

It invoked Rule 9 of the Clinical Establishments (Registration and Regulation) Act, 2010 and Clinical Establishments (Central Government) Rules, 2012, which together require that “clinical establishments shall charge the rates for each type of procedures and services within the range of rates determined and issued by the Central Government from time to time, in consultation with State Governments”. The Court ruled the Central Government Health Scheme rates as an interim measure if the government failed to find ways to regulate rates.

What are Clinical Establishments (Central Government) Rules, 2012 ?

- About:

- In exercise of the powers conferred by section 52 of the Clinical Establishments (Registration and Regulation) Act, 2010, the Central Government made the Clinical Establishments (Central Government) Rules, 2012.

- Appointment of Secretary of the National Council by the Central Government:

- The officer of the rank of Joint Secretary dealing with the subject of Clinical Establishments in the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India shall be the ex-officio Secretary of the National Council for clinical establishments established under sub-section (1) of section 3 of the Act.

- National Council and its Sub-Committees:

- The National Council shall classify and categorise the clinical establishments of recognised systems of medicine and submit the same to the Central Government for its approval. For the appointment of each sub-committee, the National Council shall define the functions of the sub-committee, number and nature of members to be appointed thereon and timeline for completion of tasks.

- At the time of formation of each sub-committee, effort should be made to ensure that there is adequate representation from across the country in each committee from experts in the relevant fields across the private sector, public sector and its organizations, non-governmental sector, professional bodies, academia or research institutions amongst others.

- The National Council shall classify and categorise the clinical establishments of recognised systems of medicine and submit the same to the Central Government for its approval. For the appointment of each sub-committee, the National Council shall define the functions of the sub-committee, number and nature of members to be appointed thereon and timeline for completion of tasks.

- Minimum Standards for Medical Diagnostic Laboratories:

- Every clinical establishment relating to diagnosis or treatment of diseases, where pathological, bacteriological, genetic, radiological, chemical, biological investigations or other diagnostic or investigative services, are usually carried on with the aid of laboratory or other medical equipment, shall comply with the minimum standards of facilities and services as specified in the Schedule.

- Other Conditions for Registration and Continuation of Clinical Establishments:

- Every clinical Establishment shall display the rates charged for each type of service provided and facilities available, for the benefit of the patients at a conspicuous place in the local as well as in english language.

- The clinical establishments shall charge the rates for each type of procedures and services within the range of rates determined and issued by the Central Government from time to time, in consultation with the State Governments.

- The clinical establishments shall ensure compliance of the Standard Treatment Guidelines as may be determined and issued by the Central Government or the State Government as the case may be, from time to time.

- The clinical establishments shall maintain and provide Electronic Medical Records or Electronic Health Records of every patient as may be determined and issued by the Central Government or the State Government as the case may be, from time to time.

What are the Various Reasons of Rising Healthcare Costs in India?

- Unregulated and Profit-Oriented Health sector in India:

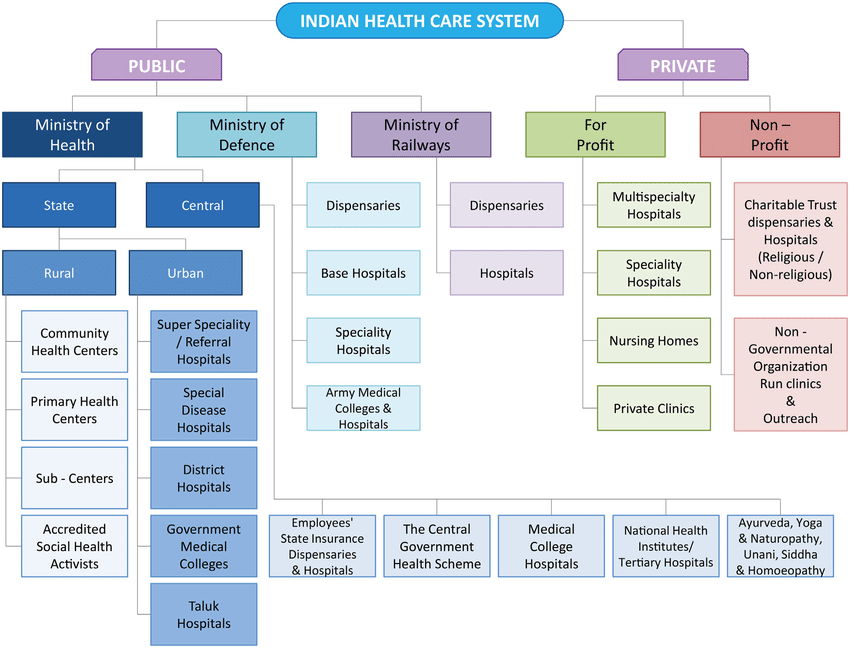

- In India, care delivery is predominantly through private providers, with market-determined prices. Health-care markets are imperfect, leading to inefficiencies and inequities and require regulation.

- In an unregulated market-driven scenario, health-care providers focus on profit through higher prices and overprovision of care (supplier-induced demand). One potential solution, “yardstick competition”, involves regulatory authorities setting benchmark prices based on market observations.

- In India, care delivery is predominantly through private providers, with market-determined prices. Health-care markets are imperfect, leading to inefficiencies and inequities and require regulation.

- However, this approach faces challenges in India due to diverse patient profiles, unreliable price data, and weak regulatory frameworks. Relying solely on competition from government hospitals is insufficient due to long wait times, perceived service quality issues, and patient information gaps, perpetuating the risk of supplier-induced demand.

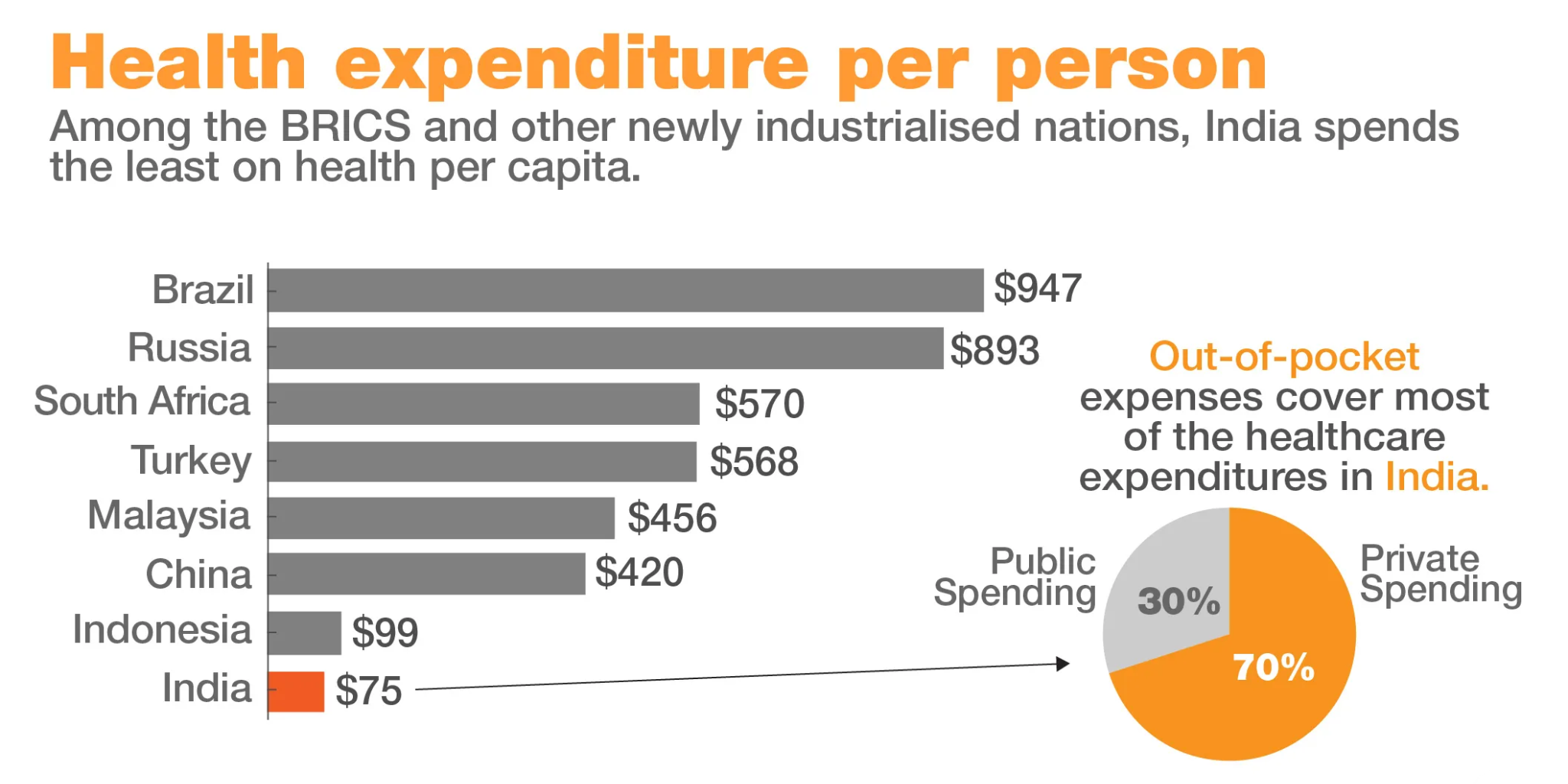

- High Out-of-Pocket Expenditures (OOPEs):

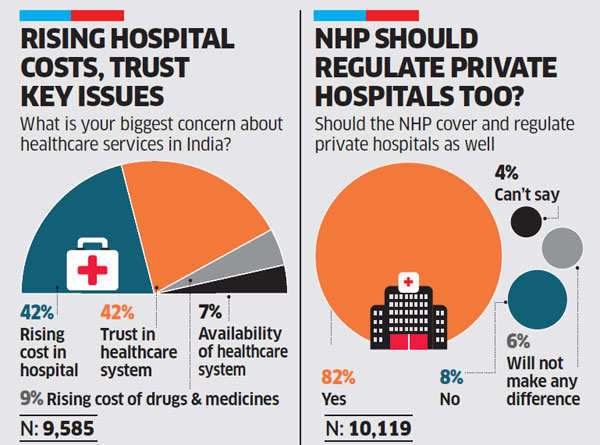

- In India, over half the total health expenditure is OOP. The other half comes from a multitude of publicly and privately pooled resources. The private sector is predominantly composed of small-scale providers. Even if rates are standardised, their implementation will be uncertain.

- Enforcement mechanisms for adherence to prescribed rates remain unclear, raising questions about the feasibility of various regulatory measures. There are concerns related to providers not adhering to the prescribed procedure rates, much like they have resisted the rates in various health schemes.

- In India, over half the total health expenditure is OOP. The other half comes from a multitude of publicly and privately pooled resources. The private sector is predominantly composed of small-scale providers. Even if rates are standardised, their implementation will be uncertain.

- Weak Implementation of Laws:

- Command-and-control regulations through pecuniary measures such as price caps can swiftly influence actors’ behaviour by making them follow the pronouncements. However, when enforcement mechanisms are weak, these effects are temporary because the overall environment remains unchanged.

- The suggested measures face enormous enforcement challenges. Only 11 States and seven Union Territories have notified the Clinical Establishment Act, 2010 and its implementation remains weak, with little or no evidence about the impact on affordability, care quality, and provider behaviour.

- Command-and-control regulations through pecuniary measures such as price caps can swiftly influence actors’ behaviour by making them follow the pronouncements. However, when enforcement mechanisms are weak, these effects are temporary because the overall environment remains unchanged.

- Issues in Capping Medical Devices:

- Design and implementation capacity constraints have hampered the effective adoption of the National Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority’s decision to cap the prices of stents and implants since 2017 and of the many directives that mandate doctors to prescribe generic medicines. Rate standardisation, through capped prices, may not address the fundamental problem of stakeholders’ misaligned incentives.

- Corporatisation of Healthcare:

- The nature of tertiary care in India changed drastically in the last three decades. Often critiqued as ‘corporatisation’ of healthcare, large tertiary healthcare providers in India earlier belonged to charitable trusts or foundations, which prioritised care over profits, unlike the present times. These hospitals employ the latest state-of-the-art technologies to mark a superior quality of healthcare. These costs are borne by the patients.

- Private practitioners, on the other hand, are under the ambit of very few rules regarding fees charged. The Clinical Establishment (Registration and Regulation) Act, 2010 sought to make treatment seeking much more transparent for patients, but many doctor associations across the country have tried to resist the enactment of the law.

- The nature of tertiary care in India changed drastically in the last three decades. Often critiqued as ‘corporatisation’ of healthcare, large tertiary healthcare providers in India earlier belonged to charitable trusts or foundations, which prioritised care over profits, unlike the present times. These hospitals employ the latest state-of-the-art technologies to mark a superior quality of healthcare. These costs are borne by the patients.

- Inadequate Investments in Public Hospitals:

- Investments in public hospitals and primary healthcare centres are not enough, given the sheer size and healthcare needs of the population. The State has historically regulated the prices of medicines via the Drug Price Control Orders, 2013 which cap the price rise of molecules, particularly for widespread and life-threatening diseases. However, medicines continue to constitute a large part of the OOPE because they are not financed by the State.

- There are shocking instances of doctor absenteeism in public healthcare, probably because of low financial incentives. There is a lack of reliable infrastructure and technologies, with only one bed available for every 2000 individuals, as per World Bank.

- Investments in public hospitals and primary healthcare centres are not enough, given the sheer size and healthcare needs of the population. The State has historically regulated the prices of medicines via the Drug Price Control Orders, 2013 which cap the price rise of molecules, particularly for widespread and life-threatening diseases. However, medicines continue to constitute a large part of the OOPE because they are not financed by the State.

- Inadequate Political Priority:

- Proliferation of the pharmaceutical industry has led to cheaper medicines for people across the world, but in India, the insidious growth of unscrupulous practices is taking a toll on the affordability of medicines.

- There is world class healthcare in urban agglomerations, but public healthcare continues to be overcrowded and underfunded. Insurance take-up is slow, and people still sell their assets to make up for healthcare costs. These major caveats in healthcare delivery and affordability show us that health is always a matter of political priority, which is lacking in the case of India.

- Proliferation of the pharmaceutical industry has led to cheaper medicines for people across the world, but in India, the insidious growth of unscrupulous practices is taking a toll on the affordability of medicines.

What are the Different Ways to Prevent the Rise of Healthcare Costs in India?

- Formulating Standard Treatment Guidelines (STGs):

- As per the observations of Supreme Court, pricing-related discussions must start with a benchmark for price determination. STGs, can help establish relevant clinical needs, the nature and extent of care, and the costs of total inputs required.

- STGs can address confounders that account for varying levels of care for various hospital procedures while ensuring clinical autonomy to respond to individual needs. Consequently, it enables valuing health-care resources consumed for the precise cost of multiple procedures.

- Given limited regulatory capacity, STG formulation and adoption require that providers’ revenues are tied to fewer payers. Providers must rely on reimbursements from pooled payments, covering most of the population with low OOP payment levels.

- As per the observations of Supreme Court, pricing-related discussions must start with a benchmark for price determination. STGs, can help establish relevant clinical needs, the nature and extent of care, and the costs of total inputs required.

- Need For a Comprehensive Health Financing Reform Strategy:

- Rate standardisation, through capped prices, may not address the fundamental problem of stakeholders’ misaligned incentives. A comprehensive health financing reform strategy informed by robust and ongoing research on appropriate processes for formulating and adopting benchmark standards must be in place, without which the actual pricing can be manipulated and justified in any manner.

- For example, hospitals with lower average revenue per bed can push their rates higher by appealing to their better care quality. Without universal standards, it will be nearly impossible to verify such claims objectively.

- Rate standardisation, through capped prices, may not address the fundamental problem of stakeholders’ misaligned incentives. A comprehensive health financing reform strategy informed by robust and ongoing research on appropriate processes for formulating and adopting benchmark standards must be in place, without which the actual pricing can be manipulated and justified in any manner.

- Following the Models of Tamil Nadu and Rajasthan:

- To finance medicines and avert margins of supply chain stakeholders, some states like Tamil Nadu and Rajasthan procure cheap unbranded generics from manufacturers and via centralised agencies sell it directly to the patients.

- Extending this to private providers also would radically change OOPE for medicines. Rolling out of insurance schemes are practical progressive steps given the dominant privatised market of healthcare.

- To finance medicines and avert margins of supply chain stakeholders, some states like Tamil Nadu and Rajasthan procure cheap unbranded generics from manufacturers and via centralised agencies sell it directly to the patients.

- Maintaining Transparency in Standardisation of Rates:

- Private healthcare providers are perhaps unique among all the commercial services in India, since the rates of their services are generally not transparently available in the public domain. This is linked with the wide spectrum of rates that may be charged for the same procedure or treatment, not only by various hospitals in the same area, but also from different patients within the same hospital.

- The Clinical Establishments (Central Government) Rules, 2012 specify that all healthcare providers must display their rates and should charge standard rates as determined by the government from time to time. However, 12 years after these legal provisions were enacted, surprisingly they are yet to be implemented.

- Private healthcare providers are perhaps unique among all the commercial services in India, since the rates of their services are generally not transparently available in the public domain. This is linked with the wide spectrum of rates that may be charged for the same procedure or treatment, not only by various hospitals in the same area, but also from different patients within the same hospital.

- Preventing Irrational Healthcare Interventions:

- It is also necessary to implement standard protocols to check irrational healthcare interventions, which are currently promoted on a wide scale due to commercial considerations.

- For example, the proportion of caesarean deliveries in India in private hospitals (48%) is three times higher compared to public hospitals (14%). In private hospitals, the share is far in excess of the medically recommended norm for caesarean sections (10-15% of all deliveries).

- Rationalising treatment practices and curbing excessive medical procedures will not just bring down excessive bills charged by many private hospitals, but also significantly improve healthcare outcomes for patients.

- It is also necessary to implement standard protocols to check irrational healthcare interventions, which are currently promoted on a wide scale due to commercial considerations.

- Implementing Patients’ Rights:

- Given huge asymmetries of knowledge and power between patients and hospitals, certain rights are universally accepted to protect patients. These include the right of every patient to receive basic information about their condition and treatment, and the expected costs of care and itemised bills; the right to second opinion, informed consent, confidentiality and choice of provider for obtaining medicines or tests; and ensuring that no hospital should detain the body of a patient on any pretext.

- Further, given the failure of existing mechanisms like Medical Councils to ensure justice for patients with serious complaints related to private hospitals, it is important that user-friendly grievance redressal systems be operationalised from district level upwards, with multi-stakeholder oversight.

- Given huge asymmetries of knowledge and power between patients and hospitals, certain rights are universally accepted to protect patients. These include the right of every patient to receive basic information about their condition and treatment, and the expected costs of care and itemised bills; the right to second opinion, informed consent, confidentiality and choice of provider for obtaining medicines or tests; and ensuring that no hospital should detain the body of a patient on any pretext.

- Controlling Commercialisation of Colleges:

- Along with these measures on private healthcare, some complementary steps concerning medical education are need of the hour. There is an urgent need to control commercialised private medical colleges, especially mandating that their fees must not be higher than government medical colleges. Further, expansion of medical education must be focused on public colleges rather than commercialised private institutions.

- Reforming National Medical Commission and NEET:

- The National Medical Commission needs independent, multi-stakeholder review and reform, keeping in view criticisms that this body lacks representation of diverse stakeholders, has excessively centralised decision-making, and tends towards further commercialisation of medical education.

- The National Eligibility-cum-Entrance Test (NEET) needs restructuring, since this tends to place candidates from less privileged backgrounds at a disadvantage, while encroaching on the autonomy of States in determining their own medical admission processes.

- The National Medical Commission needs independent, multi-stakeholder review and reform, keeping in view criticisms that this body lacks representation of diverse stakeholders, has excessively centralised decision-making, and tends towards further commercialisation of medical education.

What are the Various Government Initiatives Related to Healthcare?

- National Health Mission

- Ayushman Bharat

- Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (AB-PMJAY)

- National Medical Commission

- PM National Dialysis Programme

- Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakram (JSSK)

- Rashtriya Bal Swasthya Karyakram (RBSK)

- Increased Allocation for Health in Budget 2021.

- PM Atmanirbhar Swasth Bharat Scheme

- National Digital Health Mission

- National Medical Commission (NMC) Act, 2019.

- Pradhan Mantri Bhartiya Janaushadhi Pariyojana.

Conclusion

The observation of Supreme Court is an opportunity to create effective processes to solve a major health system problem. Rate standardisation policies must be feasible, easily implementable, and follow established price discovery practices. Future efforts must build on previous and ongoing health financing reforms, address anticipated challenges, and ensure broader stakeholder participation.

Affordable healthcare is not just a matter of providing medical treatment; it is about creating a healthcare system that respects the dignity and rights of every individual. It requires addressing the diverse needs of all people, including those who are marginalized or vulnerable, and ensuring that healthcare services are accessible, affordable, and culturally competent. Inclusive healthcare is not only a moral imperative but also a practical necessity for achieving better health outcomes for all.

|

Drishti Mains Question: Discuss the socio-economic impacts and policy measures to address the escalating healthcare costs in India, considering its implications on public welfare and economic sustainability. |

UPSC Civil Services Examination, Previous Year Questions (PYQs)

Prelims:

Q. Which of the following are the objectives of ‘National Nutrition Mission’? (2017)

- To create awareness relating to malnutrition among pregnant women and lactating mothers.

- To reduce the incidence of anaemia among young children, adolescent girls and women.

- To promote the consumption of millets, coarse cereals and unpolished rice.

- To promote the consumption of poultry eggs.

Select the correct answer using the code given below:

(a) 1 and 2 only

(b) 1, 2 and 3 only

(c) 1, 2 and 4 only

(d) 3 and 4 only

Ans: (a)

Mains:

Q.“Besides being a moral imperative of a Welfare State, primary health structure is a necessary precondition for sustainable development.” Analyse. (2021)