Governance

Federal Water Governance

This article is based on “Writing on the water” which was published in The Indian Express on 19/11/2020. It talks about the need for a systematic federal response where the Centre and the states can work together to deal with the looming water crisis.

Recently, two bills related to water governance were passed by the Lok Sabha viz. the Interstate River Water Disputes Amendment Bill 2019 and the Dam Safety Bill 2019. These bills seek to deal with the emerging challenges of inter-state water governance in India.

The Interstate River Water Disputes Amendment Bill 2019 seeks to improve the inter-state water disputes resolution by setting up a permanent tribunal supported by a deliberative mechanism the dispute resolution committee.

The Dam Safety Bill 2019 aims to deal with the risks of India’s ageing dams, with the help of a comprehensive federal institutional framework comprising committees and authorities for dam safety at national and state levels.

However, the agenda of future federal water governance is not limited to these issues alone. These include emerging concerns of long-term national water security and sustainability, the risks of climate change, and the growing environmental challenges, including river pollution.

Therefore, these challenges need systematic federal response where the Centre and the states need to work in a partnership model.

Challenges in Water Governance

- Federal Issue: Water governance in India is perceived and practised as the states’ exclusive domain. However, their powers are subject to those of the Union under Entry 56 about inter-state river water governance.

- Combined with the states’ dominant executive power, these conditions create challenges for federal water governance.

- Further, the River Boards Act 1956 legislated under Entry 56. However, till this date, no river board was ever created under the law.

- Water Knows No political Boundaries: Owing to different jurisdiction and control of states, the interconnectedness of surface and groundwater systems resulted in fragmented surface and groundwater policies.

- Also, due to this, data availability in India is currently fragmented, scattered across multiple agencies, and inadequate for sound decision-making.

- Moreover, data gaps exist on the interconnectivity of rainwater, surface water, and groundwater, land use, environmental flows, ecosystems, socio-economic parameters, and demographics at the watershed level.

Need For Cooperative Federalism

- Looming Water Crisis: A NITI Aayog report held that 21 major cities are expected to run out of groundwater as soon as 2020 which may affect nearly 100 million people.

- Moreover, the 2030 Water Resources Group projects a 50% gap between water demand and water supply in India by 2030.

- Therefore, in order to address the over-abstraction and overuse of water in multiple geographies, there is a need for the concerted effort of centre and state governments.

- Pursuing National Projects: Greater centre-states coordination is also crucial for pursuing the current national projects like Ganga river rejuvenation or inland navigation or inter-basin transfers.

- Also, the latest centrally sponsored scheme (CSS), Jal Jeevan Mission (JJM), envisages achieving universal access to safe and secure drinking water in rural areas, which otherwise is a domain of the states.

Way Forward

- Centre-States Dialogue: The Centre can work with the states in building a credible institutional architecture for gathering data and producing knowledge about water resources.

- In this context, JJM presents an opportunity to get states on board for a dialogue towards stronger Centre-states coordination and federal water governance ecosystem.

- The dialogue can consider the long-recommended idea of distributing responsibilities and partnership-building between the Centre and states, like centre can build a credible institutional architecture for gathering data and states can improve the delivery of this essential service to its populations.

- Multi-Stakeholder Approach: In view of multiple stakeholders ( farmers, urban communities, industry and government) influencing and affected by water flows, and governance framework should strive to achieve joint decision-making.

- In this context, the establishment of stakeholder councils can help to a large extent.

- Implementing Mihir Shah Committee Recommendations: There is a need to carry out some essential reforms as recommended by Mihir Shah committee. For example,

- Merging Central Water Commission and the Central Ground Water Board into one National Water Commission which would cover both groundwater and surface water issues.

Conclusion

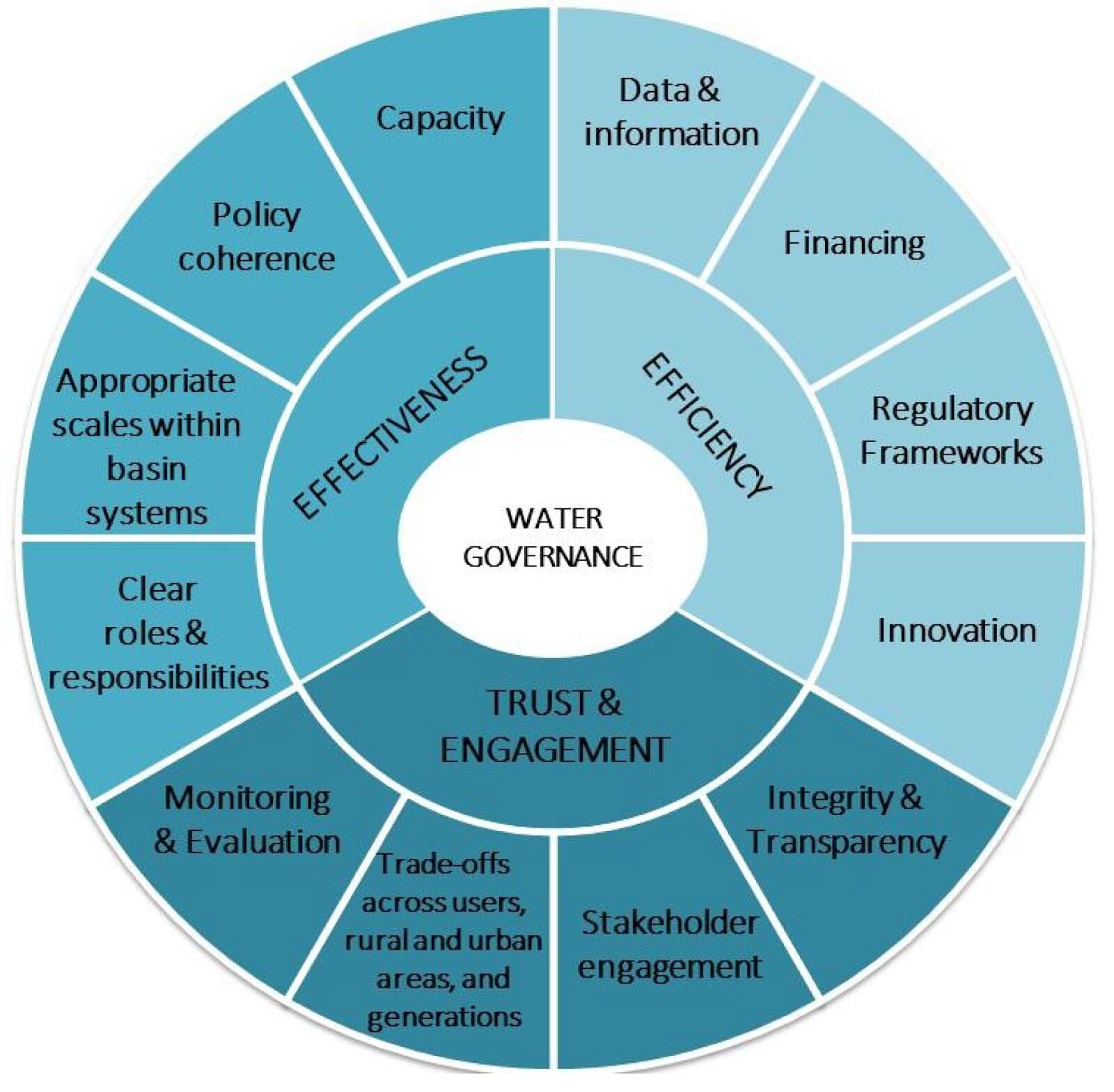

Water governance is widely acknowledged as an important factor for sustainable development. Thus, a concerted effort of all stakeholders is required for resolving conflicts and developing a shared vision for the use of water resources to support economic growth, social development and environmental protection.

|

Drishti Mains Question Good water governance needs systematic federal response where the Centre and the states need to work in a partnership model. Discuss |

This editorial is based on “Modi-Biden lay out a road map” which was published in The Hindustan Times on November 19th, 2020. Now watch this on our Youtube channel.