Governance

Making SBM-Grameen More Transformative

This editorial is based on “A critical view of the ‘sanitation miracle’ in rural India” which was published in The Hindu on 06/02/2024. The article explores the implementation of the Swachh Bharat Mission-Grameen (SBM-G) and emphasizes the necessity for the government to pinpoint any deficiencies in the current program to achieve the transition from Open Defecation Free (ODF) to ODF-Plus status by the year 2024-25.

For Prelims: Swachh Bharat Mission Grameen, Open Defecation Free Status, Gobar Dhan, Swachh Vidyalaya Abhiyan, Swaachha App, Sustainable Development Goals, United Nations.

For Mains: Issues in the Implementation of Swachh Bharat Mission-Grameen (SBM-G)

Public sanitation programmes have a long history in the country, beginning with the launch of the highly subsidized Central Rural Sanitation Programme (CRSP) in 1986. The Total Sanitation Campaign in 1999 marked a shift from a high subsidy regime to a low subsidy one and a demand-driven approach.

The public sanitation programme evolved as a mission in 2014 under the Swachh Bharat Mission-Grameen (SBM-G) to make India Open Defecation Free (ODF) by October 2019.

In the past decade, improving sanitation coverage has been one of the key public policy miracles in India. Access to water and sanitation is Goal 6 in the 17 Sustainable Development Goals envisaged by the United Nations.

What is Swachh Bharat Mission Grameen (SBM-G)?

- About:

- It was launched in 2014 by the Ministry of Jal Shakti to accelerate the efforts to achieve universal sanitation coverage and to put focus on sanitation.

- The mission was implemented as a nationwide campaign/janandolan which aimed at eliminating open defecation in rural areas.

- SBM (G) Phase-I:

- The rural sanitation coverage in the country at the time of launch of SBM (G) on 2nd October 2014 was reported as 38.7%.

- More than 10 crore individual toilets have been constructed since the launch of the mission, as a result, rural areas in all the States have declared themselves ODF as on 2nd October, 2019.

- SBM(G) Phase-II:

- It emphasizes the sustainability of achievements under phase I and to provide adequate facilities for Solid/Liquid & plastic Waste Management (SLWM) in rural India.

- It will be implemented from 2020-21 to 2024-25 in a mission mode with a total outlay of Rs. 1,40,881 crores.

- The SLWM component of ODF Plus will be monitored on the basis of output-outcome indicators for 4 key areas:

- Plastic waste management,

- Biodegradable solid waste management (including animal waste management),

- Greywater (Household Wastewater) management

- Fecal sludge management.

- Sub-Components of SBM:

- GOBAR-DHAN (Galvanizing Organic Bio-Agro Resources) Scheme:

- It was launched by the Ministry of Jal Shakti in 2018.

- The scheme aims to augment income of farmers by converting biodegradable waste into compressed biogas (CBG).

- Individual Household Latrines (IHHL):

- Under SBM, individuals get around 15 thousand for the construction of toilets.

- Swachh Vidyalaya Abhiyan:

- The Ministry of Education launched Swachh Vidyalaya Programme under Swachh Bharat Mission with an objective to provide separate toilets for boys and girls in all government schools within one year.

- Swachhta Hi Sewa Campaign:

- Swachhata Hi Seva (SHS) campaign is celebrated from 15th September to 2nd October annually under the joint aegis of Department of Drinking Water and Sanitation (DDWS) & MoHUA for undertaking shramdaan activities aimed at generating jan andolan through community participation:

- To provide impetus on implementation of SBM;

- To disseminate the importance of a sampoorna swachh village;

- To reinforce the concept of Sanitation as everyone’s business;

- And as a prelude for the Swachh Bharat Diwas (2nd October) with nationwide participation.

- Swachhata Hi Seva (SHS) campaign is celebrated from 15th September to 2nd October annually under the joint aegis of Department of Drinking Water and Sanitation (DDWS) & MoHUA for undertaking shramdaan activities aimed at generating jan andolan through community participation:

- GOBAR-DHAN (Galvanizing Organic Bio-Agro Resources) Scheme:

- Top Performing States:

- The top performing States/UTs which have achieved 100% ODF Plus villages are – Andaman & Nicobar Islands, D&N Haveli, Goa, Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu & Kashmir, Karnataka, Kerala, Ladakh, Puducherry, Sikkim, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, and Tripura.

- Among States/ UTs – Andaman & Nicobar Islands, Dadra Nagar Haveli & Daman Diu, Jammu & Kashmir and Sikkim have 100% ODF Plus Model villages.

- These States & UTs have shown remarkable progress in achieving the ODF Plus status, and their efforts have been instrumental in reaching this milestone.

- The top performing States/UTs which have achieved 100% ODF Plus villages are – Andaman & Nicobar Islands, D&N Haveli, Goa, Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu & Kashmir, Karnataka, Kerala, Ladakh, Puducherry, Sikkim, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, and Tripura.

Open Defecation Free Status

- ODF: An area can be notified or declared as ODF if at any point of the day, not even a single person is found defecating in the open.

- ODF+: This status is given if at any point of the day, not a single person is found defecating and/or urinating in the open, and all community and public toilets are functional and well maintained.

- ODF++: This status is given if the area is already ODF+ and the faecal sludge/septage and sewage are safely managed and treated, with no discharging or dumping of untreated faecal sludge and sewage into the open drains, water bodies or areas.

What are the Issues in Transitioning from ODF to ODF+ Status Under SBM-G?

- Behavioral Challenges:

- The construction of toilets does not automatically lead to their use. A National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) survey (69th round), showed that in 2012, when 59% of rural households had no access to a toilet, 4% of individuals who had access reported not using the facility.

- The primary reasons for not using one were: not having any superstructure (21%); the facility malfunctioning (22%); the facility being unhygienic/unclean (20%), and personal reasons (23%).

- The construction of toilets does not automatically lead to their use. A National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) survey (69th round), showed that in 2012, when 59% of rural households had no access to a toilet, 4% of individuals who had access reported not using the facility.

- Region Specific Challenges:

- A survey conducted in 2018, covering the best and worst covered districts and blocks of three States, showed that 59% of households in Bihar, 66% in Gujarat and 76% in Telangana had toilet access.

- Among those having access, 38% of households in Bihar, 50% in Gujarat and 14% in Telangana had at least one member who did not use it.

- A higher non-use of toilets in Gujarat was due to a lack of access to water in Dahod district, one of the two districts selected from the State.

- Toilet use is found to be very high in remote and backward villages if households have doorstep access to water. The chances of toilet use are also reduced if a household has a detached bathroom.

- Issues Due to Traditional Norms of Purity:

- In another study in 2020, it was observed that 27% of households in survey villages in Gujarat and 61% in West Bengal did not have their own toilets. Moreover, around 3% of households did not use their own toilets in either State.

- One-fourth of non-user households in Gujarat did not cite any specific reason for not using it. Social norms of purity may have dissuaded them from using the toilet.

- Toilets not used for defecation are used as storerooms. If social norms prevent toilet use on the premises, the facility is used for bathing and washing clothes.

- In another study in 2020, it was observed that 27% of households in survey villages in Gujarat and 61% in West Bengal did not have their own toilets. Moreover, around 3% of households did not use their own toilets in either State.

- Persistent Quality Issues:

- Quality issues are also another major reason. In Gujarat, 17% of those not using toilets reported that the substructure had collapsed, and 50% reported that the pits were full.

- One-third of non-users in West Bengal reported that the superstructure had collapsed, and another one third reported the pit being full.

- Variations Across Surveys Regarding Access to Toilets:

- The variations across surveys of the percentage of households having access to toilets and their use are due to the selection of different districts. The more comprehensive National Annual Rural Sanitation Survey (NARSS) Round-3 (2019-20), conducted by the Ministry of Jal Shakti, shows that 95% of the rural population had toilet access in India.

- Access to owned, shared, and public toilets was available to 79%, 14% and 1% of households, respectively. It was also reported that 96% of toilets were functional, and almost all had access to water.

- However, the same report suggests that only 85% of the rural population used safe, functional, and hygienic toilets. Assuming that the same percentage of people have toilet access as the households, the gap rises to 10% between access to toilets and their use.

- Household Size Constraints:

- Different econometric models show that along with economic conditions and education, toilet use depends on household size. The higher the household size, the greater the chances of not using the toilet.

- Overcrowding and social norms prevent all household members from using the same toilet. Our survey of 2020 shows that only 3% to 4% of households have more than one toilet.

- Different econometric models show that along with economic conditions and education, toilet use depends on household size. The higher the household size, the greater the chances of not using the toilet.

- Concerns in Phase-II of SBM-G:

- Phase II of the programme does not have any criteria mandating multiple toilets for households larger than a certain size. Neither does it have any provision for building an attached bathroom.

- Detached Role of Jal Jeevan Mission:

- The Jal Jeevan Mission (JJM) programme was launched to provide tap water to each household by 2024. Nevertheless, no relation has been observed between per capita central expenses made on the JJM and the percentage of villages declared ODF Plus across States.

- Neither is there any relation between the percentage of ODF Plus villages in a State and households having tap connections.

- The Jal Jeevan Mission (JJM) programme was launched to provide tap water to each household by 2024. Nevertheless, no relation has been observed between per capita central expenses made on the JJM and the percentage of villages declared ODF Plus across States.

- Variations Across Socio-Economic Classes:

- Sanitation behaviour also varies across socioeconomic classes. NARSS-3 finds that access to toilets was highest for upper castes (97%) and lowest for Scheduled Castes (95%). The multi-State study finds that the percentage of non-users is higher among upper castes than backward castes.

- Lack of Synergy:

- Around 10 crore toilets were constructed between 2014 and 2019 during the initial phase of the SBMG. The spurt in coverage has also triggered awareness regarding safe sanitation practices.

- However, collective behavioural change in the nation has still to take place. Our studies suggest that behavioural change in sanitation cannot happen independently.

- It is contingent upon social networks and an overall improvement of living standards, including better housing and access to basic services.

- There are separate programmes for each of these basic needs, but they are not well coordinated. The lack of overall planning in India has led to a lack of synergy of programmes despite high levels of expenditure in fulfilling basic needs.

What are the Ways to Make SBM-G More Effective?

- Mainstreaming Leftout Households:

- These surveys throw up two major issues -the leftout households and toilets unused for defecation. The leftout households appear substantial and need to be covered in Phase II.

- On the other hand, the government should identify the shortcomings of the previous phase and cover the gaps in the present phase.

- Adopting Behavioural Change Campaigns:

- Sanitation behavioural change campaigns should consider two steps: construction and use. Further, the variation in networks between villages should be considered in campaign design as in some villages, behavioural change of households can happen independently, and collectively in others.

- Phase II of the SBMG does not seem to have given enough thought to social engineering through the social networks in a society haunted by regressive norms and caste hierarchy.

- Movies like "Toilet: Ek Prem Katha" ("Toilet: A Love Story"), in which popular actors from the country play significant roles, should be screened and promoted in rural India.

- This can raise awareness among the general public about the necessity of toilet use and the adoption of hygienic and safe household sanitation practices.

- Sanitation behavioural change campaigns should consider two steps: construction and use. Further, the variation in networks between villages should be considered in campaign design as in some villages, behavioural change of households can happen independently, and collectively in others.

- Adopting an Inclusive Approach:

- Some individuals, households, and communities belonging to disadvantaged sections of society such as female-headed households, landless people, migrant laborers, and disabled people still do not have toilets in their homes or find the existing toilets not accessible.

- It is crucial to support these underserved populations both from human rights and public health perspectives because these marginalized sections are already without access to basic services and experience various health issues.

- Some individuals, households, and communities belonging to disadvantaged sections of society such as female-headed households, landless people, migrant laborers, and disabled people still do not have toilets in their homes or find the existing toilets not accessible.

- Enhanced Role Of Institutions:

- Educational institutions, child-care centers, hospitals, and other government facilities need further development in sanitation practices. Sanitation coverage of disaggregated data in public facilities and among the disadvantaged sections of society requires innovation to cover missed populations will be vital in this context.

- Following a Holistic and Extended Approach:

- Country like India, which is vast in its diversity, culture, and population, where 60% of the total population resides in rural areas, only access to toilets does not ensure hygienic and safe sanitation practices.

- For instance, the lesson from India's first sanitation program “Central Rural Sanitation Programme” launched in 1986, stated that only toilet construction did not translate to usage of toilets.

- For India to realize in achieving sustainable development goal 6 (SDG), i.e., “ensure access to water and sanitation for all” by 2030, a number of factors need to be considered cutting across social, political and economic dimensions.

- Country like India, which is vast in its diversity, culture, and population, where 60% of the total population resides in rural areas, only access to toilets does not ensure hygienic and safe sanitation practices.

- Adoption and Integration of Technologies:

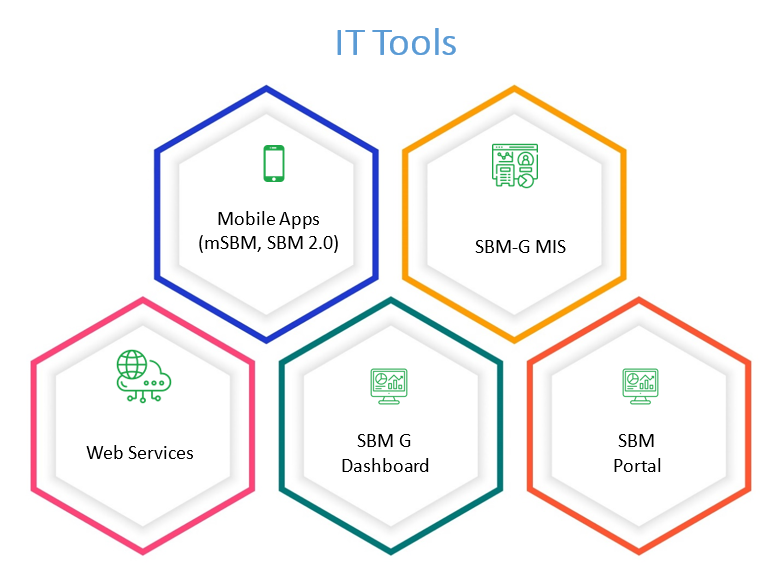

- The e-Governance Solutions need to be incorporated including Mobile Apps, MIS, dashboards APIs, developed by the National Informatics Centre (NIC), aim to track the progress of ODF Plus progress in different states.

- SBM-G e-governance solution should be a Robust, Interoperable, Scalable, Secure and Role-based system that enables user to enter all the assets of solid and liquid along with geo coordinates using mobile app.

- The e-Governance Solutions need to be incorporated including Mobile Apps, MIS, dashboards APIs, developed by the National Informatics Centre (NIC), aim to track the progress of ODF Plus progress in different states.

Conclusion

India has made notable progress in sanitation, meeting Sustainable Development Goals through initiatives like Swachh Bharat Mission. Achieving 100% sanitation coverage by 2019 is commendable, and the government aims for ODF Plus status by 2024-25. Approximately 85% of villages are already ODF Plus, but challenges remain, highlighting the need for behavioral change. Socio-economic factors and social norms require tailored approaches for sustained success.

|

Drishti Mains Question: How has the Swachh Bharat Mission Grameen impacted rural sanitation practices and what challenges remain for achieving sustainable sanitation coverage in India? |

UPSC Civil Services Examination Previous Year Questions (PYQs)

Mains:

Q. “To ensure effective implementation of policies addressing the water, sanitation and hygiene needs the identification of the beneficiary segments is to be synchronized with anticipated outcomes.” Examine the statement in the context of the WASH scheme. (2017)

Q. How could social influence and persuasion contribute to the success of Swachh Bharat Abhiyan? (2016)

Q. What are the impediments in disposing the huge quantities of discarded solid waste which are continuously being generated? How do we remove safely the toxic wastes that have been accumulating in our habitable environment? (2021)