Is taxing the Digital Economy the way to go?

Blogs Home

- 26 Jul 2019

Digitisation isn’t a new concept to the Gen Z, a supposedly tech-savvy generation that is ‘privileged’ to have been given the gift of technology in a time where we haven’t had to learn to wait.

This advancement is so normal to us now, having occupied a huge chunk in our daily lives, that we don’t stop to think and question what consequences, good or bad, may come out of this. This insurgency in the presence of the digital market and the services they provide has given rise to several business models that heavily depend on the digital and telecommunication networks.

Over the years, the digitisation of services has only grown exponentially and is still on the rise making the archaic taxation laws inapplicable, impractical, and hard to follow. France’s recent move of approving a 3% tax on revenues collected by the large digital companies in the country has generated quite a buzz and has given rise to several speculations and debates concerning how beneficial and practical it will turn out to be and whether it comes under the umbrella of fair-trade practices. This space will try to explore the move of taxing digital services and how beneficial it is for a country, taking into consideration the present Indian scenario.

First and foremost, what remains important to consider is whether a country like India even needs these taxation laws. There is no second-guessing the fact that India is finally catching up with the pace of development in the rest of the world in terms of digitisation. Especially, under the banner of the programme ‘Digital India’ launched by the current PM of India, Mr. Narendra Modi, a massive propagation of digital services is taking place. Demonetisation and Start-up India schemes have also been a propelling push on the path of information and communication technology. Furthermore, India is now one of the largest consumers of mobile data.

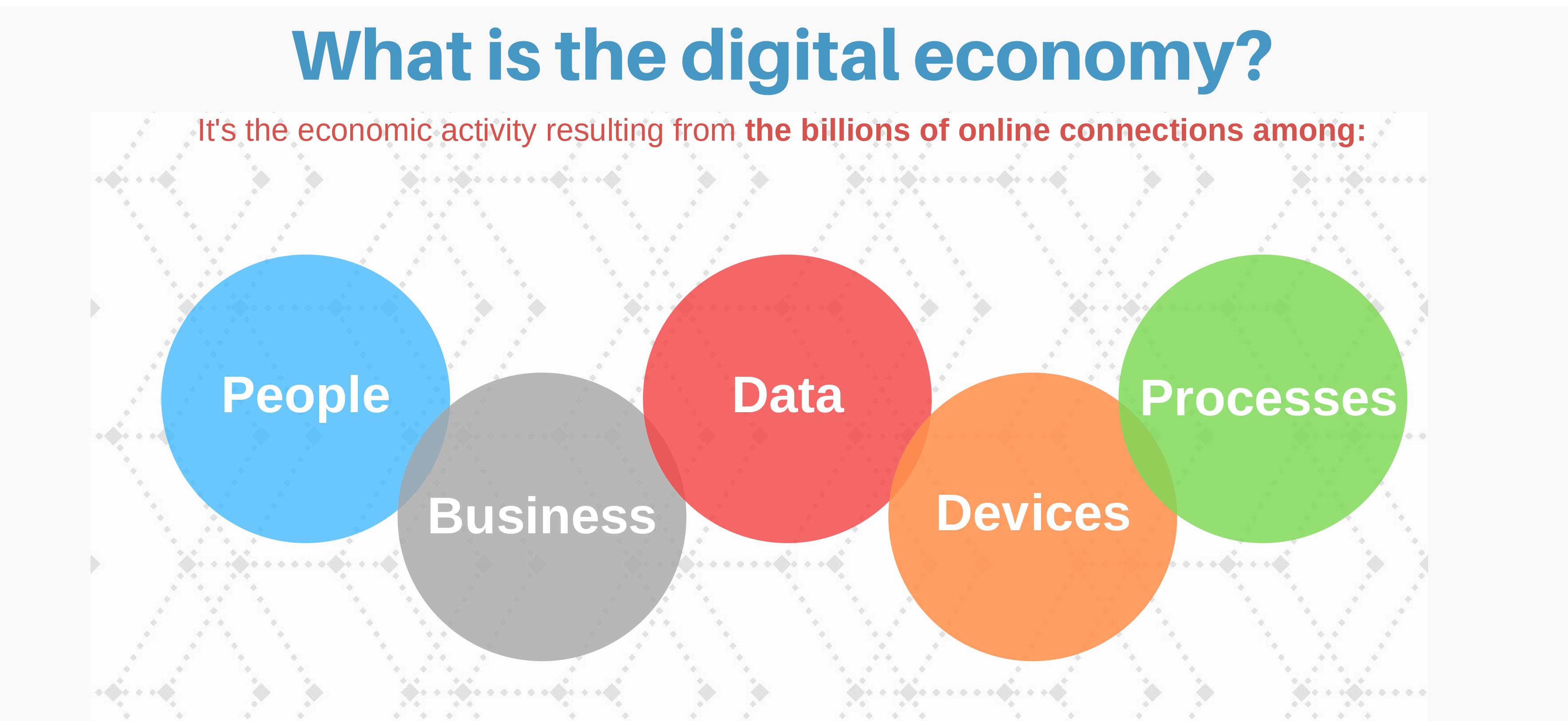

This digital economy has posed several problems on the taxation front. This new-gen economy is reliant largely on data, is very mobile, and has a spread of multi-sided business models. The unadaptive and old taxation systems which wasn’t devised for a digital world factors in and tampers with the entire symmetry of the process, and sometimes even results in a double tax burden or an excessive profit allocation.

A country can only tax a particular foreign company (a multinational company) when there has been the establishment of a ‘nexus’ through physical activity, viz. a Permanent Establishment (PE). And this is where digital businesses pose a challenge to the existing system which was built keeping the traditional businesses in mind. Digital businesses usually don't have a physical presence. They are very dependent on intellectual assets which are mobile and typically exist in (or are sent to) the low-tax jurisdictions of the world. However, like any business, digital ones too are entirely reliant on the target audience which is provided by the country of its operation. The present tax rules cannot factor in these and hence, the need for a tax re-alignment comes up.

The digital market now offers a replacement for almost everything a person needs. Mega establishments of the likes of Amazon are putting several small physical establishments out of business which in turn erodes the country’s land revenues from property taxes (and also any city’s municipal revenues). The unemployment that is caused by the closing of local businesses results in a decrease in taxes on the salaries and wages of the workers as they’ve been rendered unemployed.

And if a local establishment, owing to its physical presence, not only provides employment and livelihood but is also a responsible taxpayer, it is only fair that a digital enterprise should also hold the same level of responsibility as that local enterprise. Rishi Kapadia and Mohit Pakhecha of The Economic Times recognise this problem as that of a ‘free-rider’ that does the bare minimum but pockets all of the fruit in the basket. The remote participation of digital firms in the country’s economic welfare is one of the biggest points for taxing them. A lot of governments worldwide has acknowledged this issue. However, coming up with taxation that is fair to all has been a problem that these governments have been grappling with.

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has been debating the pros and cons of a worldwide tax. They have issued an ‘Action Plan 1’ called ‘Addressing the tax challenges of the Digital Economy’ as an aspect of its Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project (BEPS).

Though several strong points are favouring the application of tax on the digital economy, there has been a constant debate that has highlighted a few drawbacks of having such laws. The recent implication of the 3% tax by the French government has been called out as being an anti-America move. Taxation laws on ‘big’ digital companies can certainly prove to be against a particular country, considering how there is no clear distinction between ‘big-shot’ and ‘digital’ companies. France’s attempt serves as an example here, considering Trump’s threat of a lawsuit for unfair trade practices against the French. Such selective imposition of taxes and levies can often result in a violation of tax treaties and can launch an all-out trade war which will most definitely result in a decline in international trade and commerce.

There is also the concern of making these laws as equitable as possible. This makes us question a few things - would a worldwide tax mean that all digital enterprises are to pay the same percentage of their profits, regardless of their variating business models and profit turnover? Or is it going to be a remodelled version of the existing progressive tax regimes? Due to such serious concerns, it is difficult to come up with a one-fit-for-all law, making the entire situation mucky, to say the least.

Several countries, like France as mentioned here, have come up with their laws imposing levies on ‘foreign digital trades’. India too, for instance, in 2016 came up with the Equalisation Levy in the Finance Bill. It was imposed on online advertisements. It is the first instance of a digital-specific tax legislation in Indian law. The levy is applicable for consideration received by non-residents providing the following business-to-business services to a resident in India or a non-resident having a permanent establishment in India: online advertisement; any provision of digital advertising space, facility or service for the purpose of advertising; or any other service which may be notified later. There is a levy of 6% on the services mentioned above. This levy does not come under the Income Tax Act of 1961 which provides credit for taxes paid under it.

In April 2018, the concept of SEP, Significant Economic Pressure, was introduced, which triggered a possible tax for non-residents of India who have a digital presence that hasn't been specified yet. In action, it will apply to every non-resident who carries out any sort of transaction regarding goods, services or property in India. This includes the download of data and software. Owing to its somewhat open-ended definition, it is expected to take in a wide variety of transactions under its wing, though the interplay between ‘transactions’ and SEP covered under the Equalisation Levy is vague and needs more clarification.

It isn't just India and France that have realised the importance of taxing digital services and enterprises, countries like Australia, Uganda, and New Zealand have also come up with taxation schemes. In Australia, a turnover tax called ‘digital services tax’ have been proposed which may be applied to the income of large MNCs providing advertising space, trading platforms, and the transmission of data collected. New Zealand’s ‘Amazon’ tax, if implemented, will be levied on books and goods bought online. Uganda has implemented a ‘social media tax’ wherein users will have to pay a fee to use the social media platforms of WhatsApp, Twitter, and Facebook.

Now, the special cornering of American companies is blatantly obvious in the policies proposed by Uganda and New Zealand which can raise the issues that I have highlighted as the cons of digital taxes.

Even with its possible shortcomings and downsides, digital taxation can be a great step forward in the development of a country and in the better handling of future enterprises that are going to be dependent on digital infrastructures anyway. Especially, considering how vast the market has become with the implementation of schemes like Digital India and Start-Up India by the Indian Government, digital taxes, if imposed and collected with care and caution, can prove to be a very beneficial measure in the present Indian economic scenario.

We are, no matter how slowly, are progressing towards a world of cashless transactions and plastic money and with the government's efforts to push the pace of digitisation, this phenomenon is only going to accelerate. India’s national interest will be best served when the government develops a consensus-based, long-term, multilateral solution to digitisation, which includes the taxation of digital businesses by default.

Regards, Devyani

New Delhi